Exploring the Applicability of Meritocracy as a Framework for Analyzing Spatial Inequality

Abstract

This paper proposes an analytical tool for investigating spatial inequality by examining the relationship between space and meritocracy. It describes the rhetoric, research, and reality of this concept, particularly in urban planning, and provides a conceptual framework. This study posits that analogous to individuals living in a modern meritocratic society, spatial units such as cities and neighborhoods address disparity, exclusion, and morality issues. Relevant social-science literature is reviewed, including education, economics, sociology, geography, and urban planning, to consider zoning, growth management, and gentrification.

In South Korea, spatial meritocracy is particularly evident in the discrepancy between the capital region and the remainder of the county. Spatial inequality, where residents of certain neighborhoods enjoy exclusive benefits or have limited mobility within a city, is a pressing issue. By investigating the space-meritocracy relationship, this study seeks to establish a preliminary framework as well as identify the initial implications and future research directions.

Keywords:

Meritocracy, Spatial Meritocracy, Spatial Inequality, Regional Disparity, Urban Planning키워드:

메리토크라시, 공간 능력주의, 공간 불평등, 지역격차, 도시계획Ⅰ. Introduction

This study aims to explore the main issues associated with meritocracy, especially from a spatial inequality perspective, along with basic frameworks used to analyze such inequality. The focus is on shedding light on the rhetorical, research, and phenomenal aspects of meritocracy while seeking relevant frames of reference to gain insights into new perspectives in spatial interpretation.

Meritocracy, also known as a merit-based system that rewards or selects people based on their ability, effort, and performance, serves as the governing ideology and norm of modern society. That said, meritocracy is also pointed to as the cause of institutionalized inequality, which has been mainly driven by highly advanced capitalism and the rise of the super-elite. Thus, criticism of meritocracy intensifies within both academia and the real world. It seems like witnessing an “old yet new” debate.

In fact, few would concur that meritocracy is a completely new idea that has emerged in modern society. Regardless of East or West, the practice of setting ability and effort as the basis for rewards while fair competition was ensured had been commonplace in dynasty eras or under aristocratic rule. Suddenly, however, a growing number of people are raising their voices against this longstanding practice that seems reasonable and sounds like common knowledge through academic papers and newspaper articles. It appears that the situation has reached a point where criticism of meritocracy, rather than meritocracy itself, is viewed as a new school of thought. Concerns have been raised regarding the negative effect of meritocracy-blighting modern society.

As of 2024, South Korea recorded a birth rate of approximately 0.7, raising significant concerns about the state’s extinction. Even the global media is deeply concerned about the situation (BBC 2024.02.28, NYT 2023.12.02). Against this backdrop, it makes sense in a way to attribute the younger generation’s reluctance to marry and have children to the negative consequences of meritocracy-fierce competition in exams and limited generational and spatial mobility.1)

Markovits(2019) described this phenomenon as the “Meritocracy Trap,” which is also the title of the book. The author argued that meritocracy, which had emerged in response to criticism of the era of privileges driven by the idle ruling class of royals and aristocrats, led to the formation of a winner-take-all system where educational and occupational opportunities are unequally distributed among only a few people. Furthermore, their achievements would be passed down to future generations, limiting social mobility, thus creating a recurring cycle of antagonistic symbiosis-passing on their power and wealth to their descendants. Similarly, Sandel (2020) described this limited social mobility and intergenerational transmission of social and cultural capital, combined with fierce competition in seeking educational and occupational opportunities in both private and public sectors, as the tyranny of merit. The author also discussed the hardships and harm the super-elite may inflict upon themselves under this system.

In this regard, one can raise the following basic questions: What is wrong with meritocracy? Is “bad meritocracy,” rather than “good meritocracy,” a problem? How are good and evil defined in meritocracy? Is everything alright as long as opportunities are fairly and consistently offered in the first place through impartial competition, even if the results are unsatisfactory? Or do these unsatisfactory outcomes suggest that there are intrinsic defects in the workings of meritocracy? As pointed out in recent studies criticizing the negative effect of meritocracy (Cho, 2022: pp.18-25; Choi, 2023), some maintain that the neoliberal logic of viewing a level playing field as the only prerequisite to achieving equality constitutes the primary limitation of meritocracy as it is today.

This study assumes that the advantages and disadvantages of meritocracy impact regional and spatial equality in the same way they affect individuals. If apparently fair competition is ensured in urban space, would the results also be fair and sustainable? Spatial meritocracy is primarily criticized for its intrinsic, universal characteristics beyond the boundaries of time and space, such as spatial inequality, regional disparity, and spatial exclusivity. A case in point is the disparity between the Seoul Metropolitan Area and other regions of Korea. Challenges also arise when certain social groups in urban areas seek exclusive benefits or pursue exclusivity in an excessive manner. Land use zoning, growth management, and gentrification are just a few cases that represent such developments. While an approach of research that incorporates the idea of spatial meritocracy as an umbrella concept may be deemed useful and appropriate, this field remains unfamiliar territory to the academic community of land and urban studies. Therefore, this study attempts to fill the gap by focusing on the various aspects of spatial meritocracy, albeit partially.

Ⅱ. Research background and theoretical principles

1. Significance of discourse on meritocracy

By definition, meritocracy refers to a social system that rewards individuals based on their ability and performance. With a theoretical significance in social science, this norm has been embodied in a merit system that rewards and promotes individuals based on their skills and achievements both in the public sector and industry. As such, meritocracy represents the mainstream in modern organizational management. What matters now is assessing how significantly this practice affects society in reality (Lee, 2021a; Choi, 2017; Ha and Jung, 2014).

While meritocracy is increasingly at the center of attention, does it also serve as a frame of reference for analyzing modern society from an academic perspective rather than merely being used to explain specific concepts or social phenomena? Discussion on either meritocracy itself or criticism of it may provide significant implications. Meritocracy may function as a theoretical framework for the discussion of social distribution patterns, the distribution of inequality and political power, social mobility, etc. For example, it can be employed as a tool to determine whether apparent equality of opportunities and merit-based rewards actually ensure social mobility. The applicability of meritocracy as a theoretical framework can be assessed by observing the actual performance of the relevant systems, including the education system based on exams and the promotion and compensation system of the public and private sectors. This type of approach is more pronounced among those who maintain a critical stance toward meritocracy.

In his now famous satirical novel, Young (1958) proposed the requirements that leaders across various sectors, including government, business, education, and the scientific community, must meet, envisioning the future in 2033. The author highlighted traits such as intelligence, qualifications, and experience beyond simple blood ties. He conceptualized a political and social system that apparently values “each individual’s ability and effort,” overcoming plutocracy in which society is governed by aristocracy or the wealthy from birth. Additionally, the author depicted the ruling of society by a “select few wise individuals” as a normal and rational process.

The equation “IQ+Effort=Merit,” as first proposed by Young (1958), suggests that the combination of intelligence and effort represents the primary evaluation metric in that virtual society. In its early stages, meritocracy was viewed as an ideal norm that had fundamentally overturned the existing system, which was characterized by cronyism, bribery, and inheritance. However, rather than praising meritocracy as an innovative practice that stood against aristocratism, the author was much more focused on warning about its negative consequences when the idea was excessively adopted and embraced, in contrast to what the title of his novel suggested. It is reasonable to assume that this idea was initially conceptualized as the representation of “socialist criticism of inequality” and then transitioned into the “neoliberal basis for justifying inequality” (Cho, 2022). Since the 1980s, the concept has evolved into something completely positive across both sides of the Atlantic. Tony Blair, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and Gerhard Schroder, Chancellor of Germany, presented similar arguments. The discourse of upward mobility, initiated in the US in the 2000s, also stems from the idea of meritocracy (Sandel, 2020).

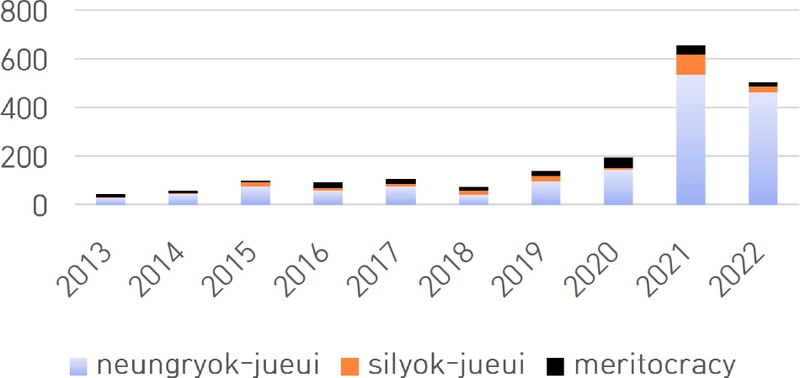

In Korea, too, meritocracy has garnered significant attention from both academia and media alike. Young (1958) anticipated that his envisioned world of meritocracy would collapse in 2033, but now, with less than 10 years remaining until that year, public discourse on this issue seems to be increasing exponentially. According to BIGKinds, a big data analysis tool for news articles in Korea, a search with keywords of meritocracy, neungryok-jueui (a Korean term referring to the ability-based system), and silyok-jueui (referring to the competency-based system) found a total of 1,793 articles dated from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2022, from the country’s 11 daily newspapers, including the Kyunghyang Shinmun, the Dong-A Ilbo, the Chosun Ilbo, the JoongAng Ilbo, and the Hankyoreh. The number of relevant articles has significantly increased since 2020 (Figure 1).

Meritocracy-related articles: Year-to-year changes in South Korean mediaNote: An analysis of 11 national daily newspapers (2013-2022), based on BIGKinds (retrieved February 23, 2023)

Moreover, Google Scholar revealed that a search with the keyword “meritocracy” resulted in approximately 162,000 documents from the global web. Among them, 895 were academic papers and documents sourced from the Korean web (with the search conducted on Google Scholar on February 29, 2024).

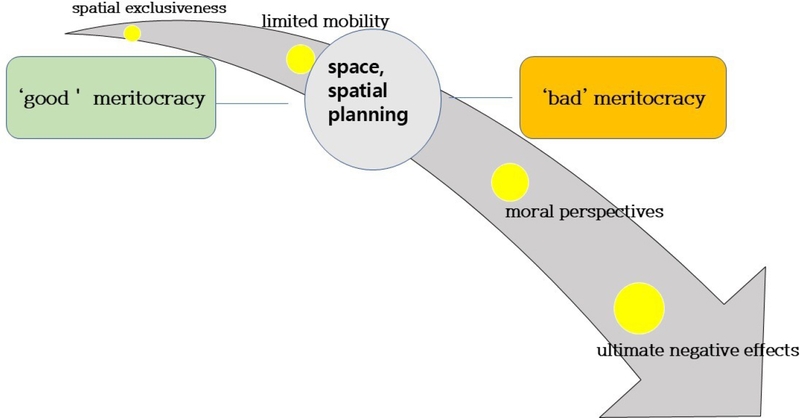

In the following chapters, issues associated with criticism of meritocracy are explored from various perspectives, especially in terms of spatial exclusivity, limited mobility, moral perspectives, and ultimate negative consequences. Through this process, the logic against the relevant general ideas can be combined with a more detailed conceptualization of meritocracy (i.e., the “betrayal of efforts,” the “meritocracy trap,” and the shared misfortune of the community as a whole). While meritocracy argues for equal opportunities, it can be theoretically interpreted in much more diverse ways by specifying critical views of meritocracy, highlighting the possibilities that it may ignore or even aggravate inequality by social background when brought into reality.

As later introduced in the discussion of spatial meritocracy, this study also pays attention to the literature of the past decade that results in significant discussion on the relevant issues at home and abroad across different disciplines of humanities and social sciences, including Education, Sociology, Geography, and Public Administration (Kim, 2018; Park, 2021; Sung, 2015; Lee, 2021a; Jang, 2011; Markovits, 2019; McNamee and Miller, 2009; Sandel, 2020).

Renowned media outlets across the globe have also increased their coverage of meritocracy or issues associated with it through articles or opinion columns. Despite slight variations depending on their political stance, criticism appears to represent the dominant perspective (NYT 2019.03.16, 2019.09.12, 2020.09.15; Economist 2018.06.12, 2020.02.08). However, the opposition is also strong. Opponents firmly advocate for modern meritocracy as a universal, broadly accepted norm (Wooldridge, 2021; Economist 2019.09.05; WSJ 2021.08.17, 2023.01.07).

Moreover, socioeconomic inequality, closely associated with meritocracy, has long been a frequent topic of academic debate, generating a substantial amount of research outcomes across a wide range of disciplines, including Economics and Sociology. Cases in point include The Price of Inequality (2013) and The Great Divide (2015), authored by J. Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics. The Capital in the 21st Century (2014) by T. Piketty must also be included. Based on statistics in the early days of 30 countries, the book analyzes changes in the proportion of capital and labor incomes, demonstrating the exacerbation of inequality from a historical perspective.

2. Spatial meritocracy

Spatial meritocracy may have greater significance when criticism of the practice, rather than the phenomenon itself, is explored. While this study provides insights into both aspects, i.e., the phenomenal characteristics of meritocracy observed in specific spaces and criticism of the relevant phenomena, to provide basic concepts and exploratory views, these two perspectives are separately treated in a discerned manner when required.

The basis for the recent criticism of meritocracy can be summarized into the following keywords: a widening gap, exclusivity, intergenerational transmission, deteriorating morality, and shared misfortune of the upper and lower classes (Markovits, 2019; Sandel, 2020; Wooldridge, 2021). That said, it is another story to determine whether such interpretations may also apply to spatial context. Unfortunately, little research has been conducted on this approach within Korea’s academic community of national land planning. It is always challenging to identify and explore new concepts and novel foundational analytical tools. This approach is deemed to be particularly timely and appropriate as it may contribute to interpreting spatial inequality, one of the primary issues considered in the recent discussion of the country’s national land use.2)

This study views spatial meritocracy as a cognitive framework or a frame of reference that externally manifests when the attributes and competencies of human groups interact with physical spaces, such as cities and regions.

Thus, spatial meritocracy embodies a wide range of social aspects, including gaps between spaces, competition and rewards, exclusivity, and long-term consequences. The nature of this discussion differs either from an approach that focuses on the functional aspects of urban planning or from demography-based research.

As a pioneer in the modern-day discussion of meritocracy, Young (1958) declared that “The soil grows castes; the machine makes classes.” Given the contextual considerations in Korea, class polarization, along with its monocentric system centered on the Seoul Metropolitan Area, the risk of extinction of local communities, and regional disparities have long been a reality in the country.

Just as individuals use the high-quality education they have received as a means to retain or raise their social class, can a space itself serve as the criterion of meritocracy from a spatial perspective? In fact, opinions may vary as to whether the proximity and accessibility of spaces, apart from their climate and geographical characteristics, may, or should, be linked to the capabilities of the corresponding spaces or individuals occupying them. Given that both human behavior and public policies are geography-bounded, it is reasonable to expect that regions or spaces may be subject to meritocracy just as individuals must be.

Against this backdrop, it would be beneficial to interpret the concepts and discussions that frequently arise in general spatial planning from a meritocratic view. Conventional practices of land use zoning, urban growth management, gentrification, and land-related taxes may be appropriate examples (Lee, 2008; Nelson, 1988; Maantay and Maroko, 2018). Additionally, discussion on growth management, growth machines, and “gated communities“ would also be helpful. These topics are worth exploring further, especially with respect to the closed nature and exclusivity of spatial value distribution. After all, these measures or outcomes are the products of competition in the context of land or space use, where entities compete against each other by leveraging their capital, knowledge, information, and political resources.

Nonetheless, it would be misguided to regard “spatial meritocracy” as an established academic term. A Google search with a keyword of the term resulted in only two documents written in English, with both being quotations (with the search conducted on Google Scholar on February 29, 2024). Most of the relevant studies discuss the general aspects of meritocracy; few attempts have been made to link meritocracy directly with spatial disparities.

3. Spatial inequality and regional disparities

Academic discussion on space basically aims to explore the interaction between humans and the spaces that surround them. Unlike disciplines of natural science, such as Physics and Geology, social science focuses on how individuals’ social behavior and economic phenomena arise in specific spaces and how they evolve over time.

Which would then make more sense: environmental determinism, a narrative arguing that physical spaces determine the behavior and culture of individuals residing in them, or environmental possibilism, which highlights the decision-making and activity of individuals over the effect of the environment (Fekadu, 2014), in addition to the broad interdisciplinary discourse driven by Diamond (1997) and other researchers aside? This question has been subject to a longstanding debate in geography. A more widely accepted perspective may lie somewhere in between the two sides, i.e., differentiating the traits and competencies of individuals deeply embedded in the spaces in which they live.

Research on space is perceived as distinct and diverse and continues evolving. For example, the primary focus of geography has been extended beyond land to include humans while paying more attention to both physical geography and urban geography. This development is perceived as familiar and understood. Additionally, attempts have been made to reconstruct major theoretical linkages in political economy from a spatial perspective (Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements, 2009: pp. 12-16; Harvey, 1982). Similarly, in sociology, more attention is now paid to the realms of spatial sociology and human ecology, and physical planning itself stands at the center of spatial research. Since the 1940s, positivism had served as the dominant paradigm of geography until it gave way to humanistic geography in the 1960s, followed by structuralism in the 1970s. This transition intensified debates over social contradictions embedded in spatial structure or regional disparities. This research trend was also in line with the aforementioned theoretical developments.

This enduring debate on spatial inequality is now represented in various forms across modern society. On a larger scale, spatial inequality is often seen as the disparity between continents or countries. On a more localized scale, it may be represented as segmented living zones and milieus (referring to the social environment) within cities such as Seoul and Daejeon (Chung, 2015). It is also worth noting that multiple academic studies on spatial disparities have been conducted over the period of a century or more, especially based in the US and other countries. Cases in point are studies by Riis (1890) and Harrington (1962).

These researchers did not attempt to directly incorporate spatial inequality into the framework of meritocracy, but their research scope was broad enough to cover the coupling of human behavior with socioeconomic phenomena across various academic disciplines associated with space use. More specifically, perspectives widely adopted in spatial economics, spatial sociology, urban geography, and urban planning may be included in the scope mentioned above.

Spatial economics raises questions regarding the reason behind the concentration of industry into specific regions or establishments. Here, special attention must be given to studies by P. Krugman and other researchers, identifying the causes of regional competitiveness and its uneven spatial distribution or accumulation across regions. This approach is deemed to have been established as a method of “new economic geography,” focusing more on the integration of individual and spatial elements while also encompassing a wide range of factors, including the interaction between increasing returns, transportation costs, and the mobility of production factors, as well as urban, regional, and international economics (Fujita et al., 1999).

Both domestic and international media outlets have also discussed issues associated with spatial disparity and inequality. For example, in 2020, the New York Times launched a long-term series of special reports titled “The America We Need,” shedding light on the reality of the US today while pointing out instances of inequality across various domains. This project, launched in 2019, continued with the outbreak of COVID-19 and spatial issues. Simply put, the pandemic situation overlapped with the combined implications of class and space.

Meanwhile, various theories have been proposed to analyze and find the causes of spatial disparities across cities or regions. Central-place theory, a traditional spatial theory developed by Walter Christaller, is introduced in most university textbooks (Christaller, 1970: pp. 601-610). Though less well known, the Third Wave Activity Theory and Urban System-Central Place Theory by Berry (1964), the spatial theory in the context of political economy by Harvey (1982), the growth coalition/growth machine theory by Logan & Molotch (1987), the uneven development theory by Smith (1984), and the spatial/geographical theory of unbalanced growth by Hirschman (1958) all provide valuable insights and implications. Although developed hundreds of years earlier in different contexts, pungsu-jiri, Korea’s traditional geomancy, Jeong Yak-yong’s anti-geomancy and anti-regional discrimination theory, and Taekriji, a geography book written by Yi Jung-hwan, also discuss spatial disparities.

Critical research on spatial environments, which has continued for the past half-century in Korea, is also noteworthy. Leading academic societies in the field of national land and urban spaces also agree that the current pluralistic public discourse on this issue begins broadening its scope through the concept of inclusive urban planning as growing attention is paid to political ecology, urban politics, geopolitics, and critical research on housing (Sonn and Lee, 2024; Park et al., 2024). It is also important to consider the intrinsic connection between space and society, as often discussed in geography, and how capital accumulation leads to urbanization in Korea (Park, 2012; Choi, 2016).

On the domestic front, regional disparity and spatial exclusivity, which represent the primary basis for criticism of meritocracy, can be demonstrated by comparing the situation between the Seoul Metropolitan Area and the rest of the nation. Given that, apart from inter-regional differences, intra-regional ones also hold significance, and one should expect that the excessive pursuit of exclusive benefits by certain social groups or regions may lead to spatial marginalization, which is characterized by housing exclusion, migration barriers, and ethical conflicts.

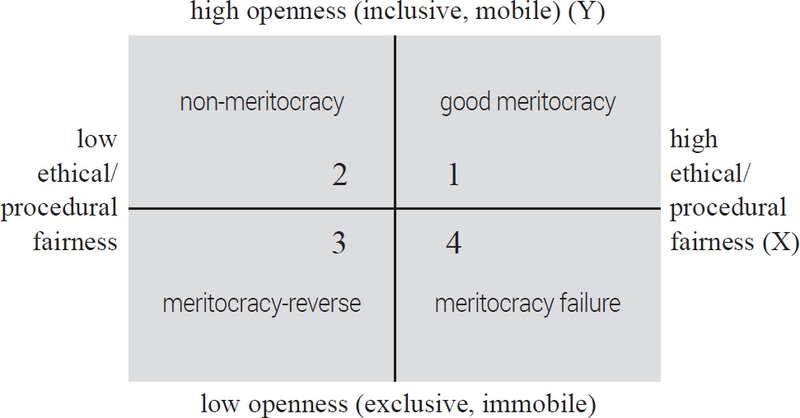

<Figure 2> presents a preliminary analytical framework, with “good meritocracy” and “bad meritocracy”, as mentioned above, set as the base line. As such, this framework gives priority to the prevailing belief that if fair procedure or competition is ensured, meritocracy will function as desired. It also assesses if the so-called “meritocracy failure” could still occur even if the competition appears to be fair. With these points in mind, Chapter III describes the applicability of meritocracy as a novel analytical framework by major discussion points.

III. Significance and key aspects of discussion on spatial meritocracy

Generally, meritocracy is discussed by pointing out both its positive and negative aspects while also focusing on relevant issues such as entry competition, performance evaluation, rewards and their impacts. In this study, criticism of meritocracy is mainly discussed in the context of space, with a special emphasis on spatial exclusivity, limited mobility, moral perspectives, and ultimate negative consequences.

1. Spatial exclusivity

Spatial planning is considered a specific form of government intervention due to market failure such as externalities or public goods. The rationale is that forming a level playing field for fair competition in urban spaces while addressing market failure will enable anyone to enter the market, compete with each other, and ultimately grow together. However, the contemporary theory of collaborative planning significantly prioritizes the communication and collaboration between interested parties, whether individuals or groups, often going beyond the realm of traditional conceptualization.

With regard to the use of land resources, does decision-making always take place based on objective and transparent criteria, such as the necessity of individuals and local communities, economic benefits, and environmental impacts? Provided that such meritocratic criteria are upheld, aren’t there any other barriers during their market entry and implementation?

In the domain of planning, policy measures that either overemphasize meritocracy or allow meritocracy to determine the outcomes of urban planning are often observed both locally and globally.

Standard instruments of conventional land use regulations include exclusive zoning, fiscal zoning, and minimum density regulations. Moreover, spatial planning, from designing urban growth boundaries to designating green belts, exerts highly specific effects on the lives and property rights of both individuals and communities. It is not an easy task to associate these effects directly with meritocracy. They may mingle with numerous other factors that take place in each space. In affluent regions, public resources, including quality schools, greenery parks, and safe pedestrian environments, become heavily concentrated based on their zoning districts and facilities established through urban planning. Unsurprisingly, this often leads to an increase in housing prices.

Establishing any form of entry barriers may result in an increase in the benefits of the inner circle but will pose greater harm at the regional or national level, as observed in past cases of regional growth management (Chinitz, 1990). Furthermore, urban planning involves numerous processes and fields that are highly ttechnical and requiring expertise. If an excessive focus is placed on expertise, or meritocratic elitism prevails, participation by ordinary citizens is restricted, and so is the diversity of outcomes.

At either the national or city level, land regulations and public goods supply are primarily governed by the self-directed efforts and competencies of individuals or local communities. In this process, however, meritocratic competition and selfishness may arise. This means that entry barriers are created, whether deliberately or not, limiting the styles or modes of living in certain spaces. For example, political dominance, information asymmetry, and the monopoly of resources hinder the entry of new individuals or groups.

The so-called exclusivity can also be found in the ongoing discussion of urban growth management. The growth management of urban areas is often viewed as a response to the sprawl of urban space, i.e., their poorly planned and unregulated planar expansion (Nelson and Duncan, 1995; Scott, 1975). Similarly, some regard it as regulations on the scale, location, and priority of urban growth as the public sector’s response to irrational developments during the process of urban growth. No matter how legitimate, transparent, and economically feasible they are, growth management efforts often end up as entry barriers for outsiders, kicking away the ladder. Indeed, it is commonly seen that such an effort is “good for the town but bad for the nation” (Lee, 2008; Chinitz, 1990; NYT 2024.03.01).

As an intra-city phenomenon, Glaeser and Cutler (2021) pointed to gentrification, or forced displacement. The authors criticized the common practice of “protecting insiders while excluding outsiders,” which entrants often face as they attempt to enter the market. Even in the world’s wealthiest cities, gentrification fuels conflicts and resentment. They argue that creating cities that are more open and dynamic necessitates lifting existing local regulations while substantially enhancing assistance for the underprivileged.

2. Limited spatial mobility

Limited spatial mobility can be largely divided into inter-regional and intra-regional types. On the domestic front, the most notable type of migration is rural-to-metropolitan area migration. In the 21st century, it is said to be almost impossible for young people residing outside the Seoul Metropolitan Area to buy homes in Seoul without any help (Park, 2023.04.03). This challenge may leave a profound, lasting impact on individuals’ psychological and moral integrity, not to mention their economic judgment, demonstrating the possibility that the inheritance of space may continue in the future.

Regarding intra-regional mobility, gentrification, as mentioned above, is associated with the migration or displacement of human populations. Over the course of gentrification, existing residents and leading industries in a certain region are replaced with those that are wealthier and operate on a larger scale. Urban regeneration or redevelopment results in fundamental changes in the physical form, demographic characteristics, and residential mobility patterns of each space as the market and capital exercise their power and influence dispassionately. During this process, the socioeconomic characteristics and cultural identity of the space also undergo significant changes accordingly (Lee and Shim, 2009; Maantay and Maroko, 2018; Nelson, 1988).

While meritocracy may be taken as the basis for justifying gentrification, this type of transition could cause significant economic and social harm to existing long-term residents and, further, even to individuals set to move in, creating a vicious cycle. Yet, it is not clear whether these developments are the enviable outcomes of market principles and economic feasibility, or they can be addressed in a preventive manner while attempting to overcome the negative consequences of meritocracy.

Entry barriers associated with spatial mobility, such as regional disparities in terms of various indicators and skyrocketing housing prices, are commonly observed and are different in nature from limited mobility at the individual level. There have recently been frequent reports of wealthy communities hindering the introduction of affordable housing complexes. While in the US, this may also be partially attributed to racial discrimination, the media seems to point to spatial exclusivity as the primary cause of these problems (NYT 2024.03.01). The situation has reached the point where even “voting with feet” is no longer an option.

3. Moral perspectives

In a fully established meritocratic system, both winners and losers are said to accept the results as they are with no or little resistance. Winners tend to take their success for granted, while losers blame themselves for their failure (Sandel, 2020; Young, 1958). However, from the standpoint of justice, despite being at the opposite ends of the philosophical spectrum, both J. Rawls and F. Hayek openly disapproved of the idea of defining justice in terms of ability or performance, suggesting that whether you have won or lost, you do not have to be either overly proud or embarrassed about the results.

Whether spatial meritocracy is morally justifiable is a critical point of discussion as it may connect deeply with individuals’ innermost emotions. This is also especially true in the presence of competition or conflicts between regions. Based on their empirical observations, Schaller and Waldman (2024) have revealed that farmers residing in underdeveloped rural areas of the US feel so humiliated and mortified that the country’s overall political society is significantly affected in a negative way. This impact extends beyond the individual level; over the course of this transition, spatial elitism occurs in a regressive manner. In Korea, there is a distinct trend toward integrating its political and economic values into a single unipolar structure centered on the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Could this transition then be attributed to the superior capabilities and morality of the corresponding space, residents, local governments, or universities? That is highly unlikely. Instead, conventional wisdom and traditional spatial theories view location as the main factor behind such concentration of resources, arguing that the proximity and access of a space to political power or capital serve as the key determinants of its superiority.

Moreover, being forcefully displaced from a place in which they live as part of a community should cause them intense emotional pain and significant financial hardship. An increase in land prices and rents resulting from urban development or regeneration is bound to exclude existing residents as capital, coupled with meritocracy, exercises its mighty power. In Korea as well, there was an urban regeneration boom for some time; however, the focus was mainly on the physical aspects of the urban environment, along with the corresponding economic changes. Rather, less attention was paid to the emotional or social aspects experienced by existing residents. Would it be appropriate for businesses that have achieved success in their development projects, or individuals moving into newly built apartment complexes thanks to meritocracy, not to feel a moral responsibility for existing residents or prospective young entrants who struggle to afford their residence owing to soaring rental prices?

4. Ultimate negative consequences

What consequences would spatial meritocracy have for the future of local communities in the mid- and long-term? A deepening gap between regions often negatively affects not only lower-tier but also high-tier domains. This issue is also commonly discussed in the criticism of meritocracy, indicating that this shift boils down to one thing—a net loss of social value.

Meritocratic events in modern society, especially in the context of space, may often escalate disparities among regions. It is likely that these regional gaps appear in the form of inequality at the global level, e.g., divides between continents or between states, or alternatively as regional inequality issues within a state. Thus, issues such as competition between regions, criteria for competition, and rewards are critical.3)

These spatial disparities are also evident within a single country, but it is still unclear whether they are the outcomes of so-called fair competition. A considerable amount of literature has been published on spatial disparity from an economic perspective for more than a century, including studies by Riis (1890) and Harrington (1962). Schaller and Waldman(2024) examined the economic downturns observed in underdeveloped rural areas and small cities in the US, with an emphasis on the resulting regional disparity. As its title literally suggests, white rural rage is erupting in an extreme manner in some regions, where the residents lag behind the advancement of technology and have a slim chance of moving into urban areas. Such dissatisfaction and resentment have directly affected their political stance, nudging them to support Donald Trump. The author warns that this transition could ultimately undermine the basis of American democracy.

Issues frequently raised in the criticism of meritocracy from a general perspective include the pain and anguish ultimately faced by the top-tier elites (Markovits, 2019; Sandel, 2020). These ultimate consequences are commonly described as the shared misfortune of the community as a whole or the “betrayal of efforts.” This largely holds true for the discussion of meritocracy from a spatial point of view.

Obvious evidence can be found in the disparity between the Seoul Metropolitan Area and the rest of Korea, which represents the most distinctive indication of the country’s regional imbalance. A wide range of indexes, including demographic, economic, and educational statistics, have demonstrated that regional disparities within the country have consistently widened over the past decades, as clearly indicated, for instance, in cartograms showing a distorted representation of population and space. Individuals also see firsthand how meritocracy enhances spatial inequality and the marginalization it causes in their daily lives. A growing number of cases show that the divide continues to widen between certain regions that possess diverse forms of capital, including educational, social, and cultural resources, along with high incomes, and the rest of the country. The Gangnam area of Seoul, Suseong-gu of Daegu, and Dunsan of Daejeon can be categorized as examples of the former.

Even in top-tier spaces, such as the Seoul Metropolitan Area, both permanent residents and transient populations often undergo severe stress and discomfort resulting from a combination of multiple factors, such as heavy traffic, unfavorable environmental conditions, outrageously high housing and education costs, and various social issues.

The excessive concentration of political, economic, and social values in Seoul, regardless of whether this trend was attributed to the unseen capabilities of the residents or the space, though highly unlikely, has caused a severe hardening of the country’s arteries; yet, this no longer grabs headlines. As pointed out by Markovits (2019), just as the top-tier elites ultimately come to suffer anguish and discomfort, those occupying upper-tier spaces also bear the pain of the so-called “betrayal of efforts” in reality.

As humanity endures and battles through years of the COVID-19 pandemic, a wide range of predictions have been made about how post-pandemic urban planning will develop, especially exploring the compatibility of density and safety. This implies that spatial factors have been significantly considered in this discussion. For example, it is easy to anticipate that there will be a safety gap based on zoning, for example, between residential or commercial areas. It is also clear that a gap exists between high-density residential areas and low-density areas of detached houses. This indicates that individuals with higher education and incomes or those residing in wealthier areas are more likely to minimize the risk of contracting the virus during the pandemic. Despite the role of the state as a coordinator being greater than ever before, the effect of spatial meritocracy is still vividly perceived (Lee, 2020; Hendrickson and Muro, 2020).

Apart from public health-related issues, such as infectious diseases, integrating spatial policy with the health of individuals or communities is also essential. Local government policies are closely associated with the health of individuals, among their primary concerns, and residents capable of organizing their space more effectively tend to remain healthier than others, even when their income levels or educational qualifications are identical.

These notions hold profound significance. An empirical analysis of health survey data of local communities also confirmed that the contextual aspects or spatial characteristics of a community significantly affected the mental health (e.g., depression) of its residents. These results highlight that even health issues, among the critical factors shaping people’s quality of life, are closely linked with the spaces they inhabit and traverse (Rho & Kwak, 2005; Park et al., 2017).

Despite a great deal of discussion on health effectiveness and health equity, determining whether these two are twin values that are compatible with each other extends beyond solely academic discourse, bearing immense significance even in reality (Lee, 2021b). In this regard, it is essential to closely examine the possibility of spatial planning suppressing the tyranny of meritocracy from a health perspective.

Discussion on health inequality, which is political in nature to some extent, may be seamlessly integrated with issues of spatial meritocracy. Here, the focus can be placed on the disparity between the Seoul Metropolitan Area and the rest of the country or on the divide between urban and rural areas. One of the most insightful references is the empirical study conducted by Khang (2015), which analyzes life expectancy across different regions based on the big data collected by the National Health Insurance Service. For example, the life expectancy at birth of the bottom 20% income group in Hwacheon-gun, Gangwon-do, was 71.0 years, the lowest in the country, while the top 20% income group in Seocho-gu, Seoul, exhibited a life expectancy at birth of 86.2, the highest in the country. This gap of 15 years may be attributed to a combination of multiple factors but still carries great weight from the perspective of spatial disparity. What has caused this situation? How can this gap be narrowed?

IV. Exploring an analytical framework

1. Key models of spatial meritocracy

In this chapter, a single model that combines the discussions described above is explored as a preliminary step. To begin with, procedural fairness, combined with the ethical perspectives discussed above, is chosen as the horizontal-axis (X-axis) variable as it serves as the major premise of modern meritocracy. Additionally, both spatial exclusivity and mobility are two key points of discussion in the discourse of spatial meritocracy, which are considered to be merged into a variable named openness. Thus, openness is plotted as the vertical-axis (Y-axis) variable. Accordingly, four quadrants are formed, as shown in <Figure 3>.

The first quadrant represents the upper right-hand corner, where both the X and Y values are positive. This ideal combination portrays good meritocracy. It may also be described as a pluralistic meritocracy where openness remains high while fair competition is ensured among those who desire to move into the local community. In contrast, the third quadrant illustrates “meritocracy in reverse,” which is considered the most regressive form of meritocracy. The fourth quadrant is a representation of meritocracy failure, which is often characterized by low openness but high levels of procedural and ethical fairness. Thus, it is also referred to as spatial elitism or incomplete meritocracy due to its combined nature of high exclusivity and low mobility. Finally, the second quadrant defines a situation where even superficial competition has no place. It may then be appropriately referred to as non-meritocracy, but its outcomes exhibit openness. Thus, ironically, critiques of meritocracy might seek to find solutions in the second quadrant, albeit partially, as competition based on ability and performance is less valued in this scenario.

2. Efficacy of analytical tools and research directions

The primary focus of this study is to assess the feasibility of exploring spatial inequality from a new perspective by considering the general criteria for or subcomponents of meritocracy. Does meritocracy or criticism of it deserve to serve as an academic analytical tool? These questions boil down to whether the application of meritocracy as a framework, similar to relevant concepts discussed in spatial planning, would be beneficial and effective in the discussion of regional disparity or inequality issues.

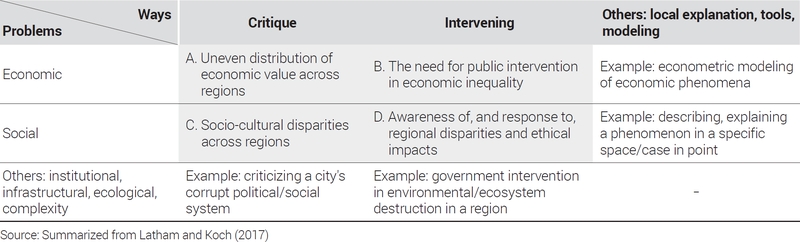

Despite not explicitly mentioning meritocracy, Latham & Koch (2017) explored how urban space had been interpreted, studied, and discussed, with a special focus on the theories and ideas of 40 modern renowned scholars of spatial studies who had established innovative theoretical foundations, encompassing a wide range of spatial planning practices. The authors first categorized both problems associated with urban space and ways of thinking about cities and then plotted them. The problem elements include six factors: economic, social, infrastructural, ecological, and complexity issues. The variables associated with the ways of thinking also embrace specific components: critique, intervention, local explanation, tools, and modeling. This approach can be integrated with the discussion of meritocracy’s feasibility as an analytical framework by interpreting the economic and social problems defined in the context of space from the perspectives of intervention and critique. Accordingly, four quadrants are created and labeled as A, B, C, and D, as shown in <Table 1>, all of which are in line with the discourse of spatial meritocracy.

The significance and efficacy of this analytical framework that explores spatial inequality from a meritocratic point of view can be emphasized as below.

First, the exclusivity or monopoly experienced by individuals attempting to enter a community, as discussed above, should be considered. These factors are rarely found in other theoretical models, such as growth machine or unbalanced growth theories. As proposed by Latham & Koch (2017), ways of thinking based on critique and criticism will primarily contribute to theorizing the process of intangible efforts to lead differentiated urban growth.

Residents with higher incomes who enjoy better living conditions are more likely to spatially exclude socially marginalized individuals or those from other local communities in a way that suits their preferences. Admittedly, even in conventional urban planning, spatial exclusivity is pursued by various policy instruments, such as exclusive zoning or fiscal zoning. Even so, in the discussion of meritocracy, it is important to observe the situation while the characteristic elements of human groups, such as their income levels and educational and cultural capital, remain deeply embedded in the spaces that they belong to.

Second, limited mobility should inevitably be taken into account. Reduced mobility perpetuates the inheritance of physical spaces. If this is the case, the fear that “The past tends to devour the future (Piketty, 2014)” could intensify across generations.

Numerous spatial studies or analytical frameworks, including unbalanced growth and urban system-central place theories, have either overlooked or paid little attention to these aspects. That said, some scholarly discussions and practical applications, such as the discourse of urban growth management, have explored exclusivity or spatial mobility to some extent. However, even these attempts have fallen short of addressing the issue of limited intergenerational mobility. In contrast, urban research, from a critical point of view, as described above, may be beneficial, whether in the context of economic or social aspects, in identifying any dynamics or asymmetric power that may be hidden in modern urban areas that are subject to limited mobility.

Third, moral and ethical consequences associated with meritocracy are rarely taken into account in the academic discourse of spatial planning. Analytical models for spatial studies, including theories of unbalanced growth, growth machine, and gated community, have rarely examined issues associated with morality. Members of local elite coalitions, described, at best, as place entrepreneurs, naturally seek their economic and political interests, as discussed by Logan & Molotch (1987). These individuals view ethical considerations as inappropriate and irrelevant to what they do. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that ethical aspects are not taken into account in those academic discussions.

Individuals who prevail in meritocratic competition are prone to arrogance, while those who lose out blame their failure on themselves. Moreover, it is still doubtful, either academically or practically, whether or not the greater social and economic benefits enjoyed by a certain group of residents or local governments are attributed to their distinguished ability or efforts. There are also many other questions, for example, regarding whether it is morally legitimate to deliberately deny individuals from a certain region opportunities to move into another and find a job. What measures should be taken to address these problems?

Fourth, unlike most spatial studies and relevant approaches, a meritocratic framework places emphasis on the misfortune shared by all community members, whether on the victorious or defeated side. For example, as the economic divide continues to widen between regions, people may begin to label one region as the “winner” and another as the “loser.” However, it is likely that, in the end, both regions will meet an unfortunate end. Even if residents of the victorious region continue to exercise their unparalleled ability, the entire land of the country will ultimately experience the onset of arteriosclerosis or the extinction of local communities. Faced with these desperate situations, it is certain that no one is exempt from their consequences. Rather than numerous analytical models for spatial planning, a meritocratic analytical framework can naturally take into account these subjects.

In addition to the relevant concepts and major issues outlined in this exploratory study, the following issues and concerns can be addressed in relation to them in a more sophisticated and empirical manner in future studies.

- i) Overview: Conceptual validity of spatial meritocracy, individual awareness of relevant issues, and their distinctive features from other concepts

- ii) Relevance of criteria for evaluating spatial meritocracy: Demographic statistics, income levels, jobs, intelligence and cognition levels, resident happiness index, political capability, etc.

- iii) Criteria for “good meritocracy”: Entry conditions, along with fairness, openness, evaluation & rewards, and morality in regional competition, etc.

- iv) Criteria for and consequences of “meritocracy failure” and “meritocracy in reverse”: Sociopolitical elements, spatial elitism, exclusivity & mobility, etc.

- v) Exploring methods for addressing the limitations of spatial meritocracy under conditions of non-meritocracy

3. Alternatives, critiquing criticism

Criticism of meritocracy has been discussed in a wide range of contexts to find alternative solutions. While novel alternatives have thus far been proposed in the literature, albeit in a fragmented manner, many of them have been hardly welcomed due to their complacent approach or low feasibility. Extreme perspectives at the opposite ends of the spectrum have also been proposed, with some even arguing that it is best to keep meritocracy as it is today, from a conservative point of view. The rationale behind their argument is Steve Jobs’s view that “Silicon Valley is meritocracy.” Some perceive this situation with a blend of self-depreciation and criticism as they have failed either to go beyond the boundaries of meritocracy or to find better alternatives, although they have maintained a critical perspective toward meritocracy.

Even at its early stages, alternatives were discussed, as demonstrated in the work of Young (1958).. His satirical fiction proposed a basic income experiment as an alternative. In the novel’s depiction of 2005, all employees are paid equally, receiving equal pay, in accordance with the Income Equalization Act (Young, 1958: pp. 148-149). This attempt is considered an act of compromise, easing dissatisfaction among the lower class.

A review of the literature from the past decade reveals that efforts have been made to explore alternatives to meritocracy, regardless of their feasibility or practicality (Markovits, 2019; McNamee and Miller, 2009; Sandel, 2020; Wooldridge, 2021). Dismissing meritocracy itself as a myth, as reflected in the title of their work, McNamee and Miller (2009) took a critical stance, highlighting its limitations across various aspects, from inheritance to education and university teaching. That said, their alternatives appear to put more emphasis on general fiscal and welfare policies. Indeed, their primary focus is on implementing various tax policies, especially, those based on the ability-to-pay principle of taxation.

Meanwhile, one of the most commonly adopted approaches to compensating for the consequences of spatial meritocracy is a deliberate effort to achieve balanced development. Yet, the question is whether this approach can prove effective and sustainable in the long run, overcoming the limitations of the uneven development theory by Smith (1984) or the theory of unbalanced growth by a group of researchers, including Hirschman (1958). Regarding the regional disparity currently experienced by Korea, there is a growing voice that ensuring a level playing field is the top priority as it no longer makes sense to force its entire people, regardless of the region, to continue their competition in a tilted playing field as it is today. Even if the country’s competition system is changed as desired, doubt will still remain about the practical efficacy of balanced development efforts. Additionally, various relevant policies, such as establishing a Multifunctional Administrative City (Sejong), relocating public organizations into local areas (Innovative Cities), and implementing the regional quota system, are still considered to have been rather less effective.

Meanwhile, measures to address inner-city gentrification have also been proposed within the country. Good examples are the policies put in place by Seoul, Gwangju, Sejong, and other local governments, such as ‘Inclusive Zones,’ rent control, tenant protection measures, and community land trust.

In Korea, spatial/social exclusion or inequality has been acknowledged for centuries, dating back hundreds of years, not to mention modern times. This awareness materialized as Jeong Yak-Yong’s anti-geomancy and anti-regional discrimination theory during the 18th century and later as the 21st century’s national balanced development theory. In recent years, demand for “nationwide decentralization and metropolitan centralization” has gained momentum.

The alternative approaches, as described above, may also be subject to criticism. For example, they are considered less feasible and require substantial physical/non-physical costs. Moreover, the point that meritocracy still holds grave value should not be overlooked.

V. Closing remarks

This exploratory study comprehensively examines the rhetoric, research literature, phenomenological trends, and analytical tools that are associated with spatial meritocracy.

This paper can be summarized as follows. First, this study aims to provide insights into a comprehensive knowledge of criticism of modern meritocracy and implications of spatial meritocracy on which groups of scholars and researchers have focused over the past decades. The primary focus is on reviewing and assessing emerging opinions on such criticism voiced by this prevailing school of thought and the framework for justification that they employed while taking a broad view of the relevant issues. The rationale behind this work’s particular focus on meritocracy from a spatial perspective is that this issue has not received the proper attention that it deserves for its significance and influence in real-life settings.

Second, among Korea’s academia and public sectors, meritocratic perspectives have been proposed and implemented in practice while being referred to as the merit or performance-based system. While, rather, it seems like witnessing a “new yet old” debate, this research holds significance in its contribution to raising questions about the philosophy embedded in relevant policies and practices from the perspective of spatial planning, along with providing new analytical tools as alternatives.

Third, discourse on the distribution of social systems and spatial values has the potential to bring tangible benefits to the world, provided that it can be extended beyond mere academic discussion to the exploration of alternatives. The point that the utility/value of society is accordingly reduced, not partially but totally, must not be overlooked. In fact, raising questions about spatial meritocracy is just like questioning the legitimacy of common sense, which has long been widely accepted in daily life. As the ancient Greek philosopher Plato once taught, it is not right to continue to uphold the so-called noble lie, a narrative arguing that social harmony can be maintained when individuals believe that inequality is legitimate despite not being true. Now is the time to ask if the disparity between spaces apparent in today’s society is also the outcome of this ideology. This also applies to common questions, such as “What has caused the incompetence of local communities?” (Ha, 2023). Research on spatial meritocracy offers a clear pathway toward finding a solution to this question.

Admittedly, this study is limited in terms of academically defining spatial meritocracy and addressing relevant issues in a meticulous manner. Indeed, it is even more challenging to prove the validity of criticism of either general or spatial meritocracy in an empirical and detailed manner by projecting them onto real-life socioeconomic phenomena. Additionally, this study could be further improved in comprehensively reviewing and summarizing relevant concerns and issues discussed across various academic disciplines, including urban geography, spatial economics, and spatial sociology, in more detail. There is also room for further improvement, especially in the study’s attempt to compare discourse on meritocracy with existing analytical frameworks that account for spatial inequality. A more thorough comparison could result in a deeper understanding of its current standing as a theoretical framework. For that purpose, this study focuses solely on the comparison of meritocracy with a few neoclassical theories. The hope is that these shortcomings will be supplemented through future studies.

Notes

References

-

Bank of Korea, 2024. BOK Economic Research Report: Limitations of Test-Centric Talent Selection and Alternatives, September 2024.

한국은행, 2024. 「BOK 경제연구 보고서: 시험 위주의 인재 선발의 한계와 대안」, 2024. -

Berry, B.J.L., 1964. “Cities as systems within systems of cities”, Papers in Regional Science, 13(1): 147-163

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5597.1964.tb01283.x]

-

Chang, E., 2011. “‘The Rise of the Meritocracy’ in Korean Society and Its Education Problem: In Searching for the Democratic Justice”, Journal of A Society for The Research of Society and Philosophy, 21: 71-106.

장은주, 2011. “한국 사회에서 ‘메리토크라시의 발흥’과 교육 문제”, 「사회와 철학」, 21: 71-106. -

Chinitz, B., 1990. “Growth Management: Good for the Town, Bad for the Nation?”, Journal of the American Planning Association, 56(1); 3-8.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369008975739]

-

Cho, H.K., 2022. “Meritocracy, Breaking away from the Paradoxical Way of the Word and Discourses”, Critical Review of History, 140: 8-32.

[

https://doi.org/10.38080/crh.2022.08.140.8

]

조형근, 2022. “능력주의, 말과 담론이 걸은 역설의 길을 벗어나기”, 「역사비평」, 140: 8-32. -

Choi, B.D., 2016. “Process of Capital Accumulation and Urbanization in S.Korea: Urban Crisis and Alternatives”, Journal of the Economic Geographical Society of Korea, 19(3): 512-534.

[

https://doi.org/10.23841/egsk.2016.19.3.512

]

최병두. 2016. “한국의 자본축적 과정과 도시화: 도시 위기와 대안”, 「한국경제지리학회지」, 19(3): 512-534. -

Choi, Y., 2023. “A Politico-Historical Reconstruction of Korean Meritocracy”, Economy & Society, 137: 245-250.

[

https://doi.org/10.18207/criso.2023..137.245

]

최율, 2023. “한국형 능력주의의 정치역사적 재구성”, 「경제와 사회」, 137: 245-250. -

Choi, Y.J., 2017. “Performance-related Pay in Government: Present Challenges and Suggestions for the Future”, Korean Public Personnel Administration Review, 16(1): 75-102.

최유진, 2017. “우리나라 공무원 성과급제도의 현황과 개선방안 연구”, 「한국인사행정학회보」, 16(1): 75-102. - Christaller, W., 1972. How I Discovered the Theory of Central Places: A Report about the Origin of Central Paces in English, P.W. and Mayfield, R.C. eds., Man, Space, and Environment: Concepts in Contemporary Human Geography, NY: Oxford University Press.

-

Chung, S.K., 2015. “Spatial Inequality of Milieus due to Living Space Differentiation: Based on the Example of Daejeon Residents”, Journal of Social Science, 26(2): 315-341.

[

https://doi.org/10.16881/jss.2015.04.26.2.315

]

정선기, 2015. “생활권 분화에 따른 밀류(Milieus)의 공간적 불평등: 대전광역시 주민의 사례를 중심으로”, 「사회과학연구」, 26(2): 315-341. - Diamond, J., 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel, New York: W.W. Norton.

- Economist, 2018.06.12. “China’s Political Meritocracy Versus Western Democracy”..

- Economist, 2019.09.05. “Affirmative Action Strengthens a Meritocracy”.

- Economist, 2020.02.08. “Are Test Scores the Backbone of Meritocracy or the Nexus of Privilege?”.

-

Fekadu, K., 2014. “The Paradox in Environmental Determinism and Possibilism: A Literature Review”, Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 7(7): 132-139.

[https://doi.org/10.5897/JGRP2013.0406]

-

Fujita, M., Krugman, P., and Venables, A.J., 1999. The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions, and International Trade, Boston: The MIT Press.

[https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6389.001.0001]

- Glaeser, E. and Cutler, D., 2021. Survival of the City: Living and Thriving in an Age of Isolation, New York: Penguin Press.

-

Ha, H.S. and Jung, K., 2014. “The Effects of Performance-based Pay from the Experience of Eleven Public Enterprises”, Korean Journal of Public Administration, 52(3): 145-177.

하혜수·정광호, 2014. “성과중심 보수제의 효과분석: 국내 11개 공공기관의 성과급”, 「행정논총」, 52(3): 145-177. -

Ha, S.W., 2023. “How Have Non-capital Regions Become Places of Incompetence?”, Today’s Education, 72: 122-131.

하승우, 2023. “지방은 어떻게 무능력한 공간이 되었을까: 능력주의와 지역 격차”, 「오늘의 교육」, 72: 122-131. - Harrington, M., 1962. The Other Americans: Poverty in the United States, London: Macmillan Publishing Company.

- Harvey, D., 1982. The Limits to Capital, Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hirschman, A.O., 1958. The Strategy of Economic Development, New Haven: Yale University Press.

-

Khang, Y.H., 2015. “Disparities in Life Expectancy by Income Level in Metropolitan Cities, Provinces, Counties, and Districts in South Korea”, Healthcare Big Data Open Second Year’s Study Performance Sharing Symposium, Seoul.

강영호, 2015. “우리나라 광역시·도와 시·군·구의 소득수준별 기대여명 차이”, 건강보험 빅데이터 개방 2차년도 연구성과 공유 심포지엄, 서울. -

Kim, B.C., 2018. “The Problem of Social Justice in Meritocracy”, The Journal of the Humanities for Unification, 73: 173-205.

[

https://doi.org/10.21185/jhu.2018.3.73.173

]

김범춘, 2018. “메리토크라시에서의 사회정의의 문제”, 「통일인문학」 73: 173-205. -

KRIHS, 2009. Pioneers in Modern Spatial Theories, Seoul: Hanul Books.

국토연구원, 2009. 「공간이론의 사상가들」, 서울: 도서출판 한울. - Latham, A. and Koch, R., Eds., 2017. Key Thinkers on Cities, 1st Edition, London: Sage Publishing.

-

Lee, H.Y. and Shim, J., 2009. “The Residential Mobility Pattern and Its Determinant Factors of Gentrifiers in Seoul”, Journal of the Korean Urban Geographical Society, 12(3): 15-26.

이희연·심재헌, 2009. “서울시 젠트리파이어의 주거이동 패턴과 이주 결정요인”, 「한국도시지리학회지」, 12(3): 15-26. -

Lee, S.C., 2008. “Critical Review of the American-style Growth Management: Research, Policy and Applicability in Korea’s Regional Cities”, Korean Public Administration Quarterly. 20(3): 713-742.

이시철, 2008. “미국형 성장관리의 비판적 고찰: 연구, 정책 그리고 우리 지방도시에의 적용성”, 「한국행정논집」, 20(3): 713-742. -

Lee, S.C., 2020. “Exploring Compatibility of Density and Safety: An Inquiry on Spatial Planning Shift in COVID-19 Era”, Journal of Korea Planning Association, 55(5): 134-150.

[

https://doi.org/10.17208/jkpa.2020.10.55.5.134

]

이시철, 2020. “밀도와 안전의 공존 가능성: 코로나19 시대, 공간계획의 변화 방향 예측”, 「국토계획」, 55(5): 134-150. -

Lee, S.C., 2021a. “Analyzing Key Issues in Meritocracy: A Focus on the Public Sector”, Korean Public Administration Quarterly, 33(4): 711-734.

[

https://doi.org/10.21888/KPAQ.2021.12.33.4.711

]

이시철, 2021a. “메리토크라시의 주요 쟁점 분석: 공공 영역을 중심으로”, 「한국행정논집」, 33(4): 711-734. -

Lee, S.C., 2021b. “Reconciling Health-effectiveness and Health-equity of Local Policies”, Space and Environment, 31(4): 171-197.

이시철, 2021b. “지역정책의 건강효과성과 건강형평성: 상충과 어울림”, 「공간과 사회」, 31(4): 171-197. -

Logan, J.R. and Molotch, H.L., 2007. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place, 20th Anniversary Edition 2007, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520934573]

-

Maantay, J.A. and Maroko, A.R., 2018. “Brownfields to Greenfields: Environmental Justice versus Environmental Gentrification”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10): 2233.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102233]

- Markovits, D., 2019. The Meritocracy Trap: How America’s Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite, London: Penguin Press.

- McNamee, S.J. and Miller Jr., R.K., 2009. The Meritocracy Myth, 2nd ed., Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Nelson, K. 1988. Gentrification and Distressed Cities: An Assessment of Trends in Intrametropolitan Migration, Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press.

- Nelson, A.C. and Duncan, J.B., 1995. Growth Management Principles and Policies, UK: Routledge.

- New York Times (NYT), 2019.03.16. “The Scandals of Meritocracy”..

- New York Times (NYT), 2019.09.12. “The Meritocracy Is Ripping America Apart”..

- New York Times (NYT), 2020.09.15. “What’s Wrong With the Meritocracy”.

- New York Times (NYT), 2023.12.02. “Is South Korea Disappearing?”.

- New York Times (NYT), 2024.03.01. “Developers Got Backing for Affordable Housing. Then the Neighborhood Found Out”.

-

Park, B.G., 2012. “Looking for More Space-sensitive Korean Studies”, Journal of the Korean Geographical Society, 47(1): 37-59.

박배균, 2012. “한국학 연구에서 사회-공간론적 관점의 필요성에 대한 소고”, 「대한지리학회지」, 47(1): 37-59. -

Park, D.H., 2023.4.3. “‘Impossible My Home’... Three out of 100 Apartments in Seoul Affordable for Median Income”, Yonhap News.

박대한, 2023.4.3. “‘불가능한 내 집’... 서울서 중위소득 구매가능 아파트 100채중 3채”, 연합뉴스. -

Park, K., 2021. “Perception and Characteristics of Meritocracy in Korea”, Ctizen & the World, 38: 1-39.

[

https://doi.org/10.35548/cw.2021.06.38.1

]

박권일, 2021. “한국의 능력주의 인식과 특징”, 「시민과세계」, 38: 1-39. -

Park, K.D., Lee, S., Lee E.Y., and Choi, B.Y., 2017. “A Study on the Effects of Individual and Household Characteristics and Built Environments on Resident’s Depression –Focused on the Community Health Survey 2013-2014 of Gyeonggi Province in Korea”, Journal of Korea Planning Association, 52(3): 93-108.

[

https://doi.org/10.17208/jkpa.2017.06.52.3.93

]

박근덕·이수기·이은영·최보율, 2017. “개인 및 가구특성과 물리적 환경이 거주민의 우울에 미치는 영향 연구 –경기도 지역사회건강조사 2013-2014 자료를 중심으로”, 「국토계획」 52(3): 93-108. -

Piketty, T., 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674369542]

-

Rho, B.I. and Kwak, H.K., 2005. “A Study on the Effect of Neighborhood-Level Contextual Characteristics on Mental Health of Community Residents”, Health and Social Science, 17: 5-31.

노병일·곽현근, 2005. “동네의 맥락적 특성이 주민의 정신건강에 미치는 영향: 동네빈곤, 무질서, 네트워크 형성을 중심으로”, 「보건과 사회과학」 17: 5-31. - Riis, J., 2005. How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York, US: Digireads.com.

- Sandel, M.J., 2020. The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Schaller, T.F. and Waldman, P., 2024. White Rural Rage: The Threat to American Democracy, New York: Random House.

- Scott, R.E., 1975. Management & Control of Growth, Washington DC: Urban Land Institute.

- Smith, N., 1984. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space, University of Georgia Press. – Alan Latham & Regan Koch. Key Thinkers on Cities (p. 171), SAGE Publications. (Kindle Edition)

-

Sonn, J.W. and Lee, H., 2024. “Critical Approaches in Spatial and Environmental Research: Past, Present, and Future”, Space and Environment, 34(1): 4-6.

손정원·이후빈, 2024. “비판적 공간환경 연구의 과거, 현재, 미래”. 「공간과 사회」, 34(1): 4-6. - Stiglitz, J.E., 2013. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, London: Penguin Press.

- Stiglitz, J.E., 2015. The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them, New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

-

Sung, Y.K., 2015. “From Meritocracy to Democracy: With Reference to Michael Young’s Discussion”, Korean Journal of Educational Research, 53(2): 55-79.

성열관, 2015. “메리토크라시에서 데모크라시로: 마이클 영(Michael Young)의 논의를 중심으로”, 「교육학연구」, 53(2): 55-79. - The Wall Street Journal (WSJ), 2021.08.17. “Meritocracy Is Worth Defending”.

- The Wall Street Journal (WSJ), 2023.01.06. “Upward Mobility Is Alive and Well in America”.

- Wooldridge, A., 2021. The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World, New York: Skyhorse Publishing.

- Young, M., 1958. The Rise of the Meritocracy, U.K.: Pelican Books.

- BBC, 2024.02.28. “South Korea Says Its Birth Rate Has Fallen to a Record Low”, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w172z07gqg2dw48, .

- Hendrickson, C. and Muro, M., 2020.04.12. “Will COVID-19 Rebalance Americas Uneven Economic Geography? Don’t Bet on It”, Brookings Institution United States of America, https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/zn4n55