A Study on the Idea of Heavy Taxation on the Unearned Income from Real Estate and Gradual Institutional Change focusing on Land Excess-Profit Tax and Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax in Korea

Abstract

The objective of this study is to explain the policy changes in heavy property tax that led to the introduction of the Land Excess-Profit Tax (LEPT) in 1989 and the Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax (CREHT) in 2005, based on the theory of gradual institutional change. Both the LEPT and the CREHT are grounded in the public concept of land, which holds that speculative rent should be absorbed by the public. However, the specific forms of these policies have gradually changed through a process of conversion, drift, and layering. The LEPT, one of the three laws embodying this public concept, was introduced in 1989 by the Roh Tae-woo government through conversion. However, tax resistance emerged as a side effect because the operation did not fulfill its original purpose, leading to its abolition in 1997 due to the IMF's foreign exchange crisis. It was then converted into the CREHT in 2005 by the Roh Moo-hyun government. The CREHT strengthened the existing comprehensive land tax to replace the unconstitutional LEPT and differed from the LEPT by imposing taxes on excess property tax bases. Nevertheless, it faced neutralization due to tax resistance, and an unconstitutional ruling by the Constitutional Court during the Lee Myung-bak administration. It has since been repeatedly tightened and loosened by successive governments. The concept of heavy property tax, initially a rent tax based on the public concept of land, has primarily been used to curb speculation during periods of rapidly rising real estate prices. Compared to the LEPT, the CREHT demonstrated institutional flexibility by adjusting the function of heavy taxation as needed and was used to curb real estate speculation and tax the wealthy. Even if the CREHT is repealed, the idea of heavy property tax could potentially be absorbed into the existing property tax system.

Keywords:

Tax on Land Rent, Gradual Institutional Change, Idea Theory, Land Excess-Profit Tax (LEPT), Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax (CREHT)키워드:

지대조세, 점진적 제도변동, 아이디어 이론, 토지초과이득세, 종합부동산세Ⅰ. Introduction

1. Research background and purposes

Korea's comprehensive real estate holding tax (CREHT), which has been put in place for the last two decades, is now at the center of attention as many argue for relaxing or even repealing the tax scheme (Lee & You, 2024; Kim, 2024). Since its 2005 introduction by the Roh Moo-hyun administration, CREHT had sparked fierce debate from the outset, triggering resistance from taxpayers. In 2008, the Constitutional Court declared the tax policy unconstitutional. Meanwhile, among the country's three acts that uphold the public concept of land, the land excess-profit tax (LEPT) is similar to the CREHT. The LEPT is rooted in the ideas that an increase in the value of land, especially idle parcels, should be taxed to discourage the speculative holding of land, and that individuals should accept regulations on their land property rights, provided that such movement is intended for public welfare (Song & Kim, 1990). Viewing land rent income as predatory gains obtained by exploiting their monopolistic position or simply as unearned income naturally leads to the conclusion that the government should publicly recapture an excessive portion of it. At times, however, such attempts face intense resistance (Lee, 1987; Ricardo, 2010; George, 1997).

For example, fierce tax resistance from those subject to the CREHT emerged as one of the most critical issues in the country's 20th presidential election in 2022 (Kim, 2023). The CREHT was initially designed to tax large-scale real estate owners whose income exceeds a certain tax base. In reality, however, the scope of taxable subjects began to be extended to include even the middle class, imposing heavy taxation on them as housing prices surged in 2020. Although this controversy repeated itself each time real estate prices hiked, starting in the early 2000s (Kim, 2016), it was difficult to initiate a comprehensive discussion on the issue because little research had been conducted to explore the origin of the tax scheme or the initial intent of introducing it (Yoo, 2004; Park, 2004; Kim, 2004; Kim, 2007; Kim, 2009).

Historical institutionalism, a social science approach that emphasizes the path dependence of institutions, was criticized for its exclusive focus on the inertial retention of institutions at its early stages. However, since the 2000s, the approach has aggressively embraced concepts of ideas, thereby evolving itself as an effective means to address longterm dynamics of change (Blyth et al., 2016; Mahoney & Thelen, 2010; Béland, 2005). Similar to other neo-institutional perspectives, historical institutionalism has extended the scope of research to include non-official institutions, such as custom and implicit rules (Yoo & Seo, 2014), but it differentiates itself from others by focusing on the historical and contextual aspects of institutions, proving that it serves as the direct successor of traditional institutionalism (Rousseau, 2018; Fioretos et al., 2016).

Meanwhile, in urban planning and real estate policymaking, perspectives based on historical institutionalism have been consistently in the limelight. Shin (2013) shed light on changes in urban management planning from institutional perspectives. Kim & Seo (2014) analyzed changes in Sejong City's urban policy, while Seo & Kim (2017) explored path dependence found in the regulatory policy of the Seoul Metropolitan Area. With regard to historical institutionalism, in particular, Yoo & Seo (2014) studied changes in the country's land readjustment projects, while Nam (2017) addressed the functional change of the country's local Techno-Parks. Cho (2017) focused on changes in the financial system in real estate development. Lim (2022) examined the establishment of the country's new town ideas, while Heo (2023) discussed changes in the country's housing policy.

This study aims to examine major milestones in the history of the country’s LEPT and CREHT and, therefore, prove that such developments have been part of gradual institutional changes based on the idea that unearned income from real estate should be subject to heavy taxation. To this end, both historical institutionalism and the theory of gradual institutional change are introduced, and analytical frameworks built on them are examined. This study also focuses on how the government, from the Roh Tae-woo administration to the Yoon Seok-yul administration, as a policy provider, has introduced and implemented each policy, as well as how the general public, as the policy recipients, has responded to them. The major findings of this study are expected to provide valuable insights into how individual policies or policy ideas continue to evolve over a long period of time while consistently interacting with one another.

Ⅱ. Theoretical Ground and Literature Review

1. Historical Institutionalism, Gradual Institutional Change, and Ideas

In historical institutionalism, institutions are defined as “stylized patterns of human behavior established for a long period of time,” with a special focus on both official and non-official constraints that affect the behavior and decision-making of individuals and their groups (Ha, 2016). In this respect, institutions remain as they are, driven by the inertial of path dependence, until they may be subject to fundamental change due to external shocks, such as economic crises or military conflicts (Krasner, 1988). However, it is rare in reality that abrupt changes are made to existing institutions. Accordingly, new perspectives began to emerge that regarded institutions not as individual entities but as complexes of various subcomponents. The idea was that these subcomponents were created at different times and for different purposes, and variations in them may cause gradual changes in the corresponding institutions (Kim, 2023: p.335).

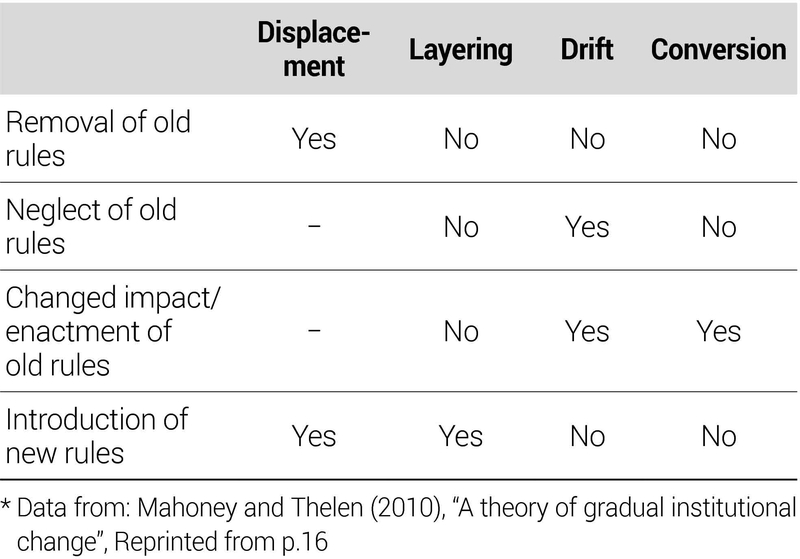

Mahoney & Thelen (2010) supplemented a study by Streeck & Thelen (2005), proposing the following four types of gradual institutional changes: displacement, layering, drift, and conversion. Displacement refers to a practice of eliminating existing institutions and introducing new ones, while layering represents a process of introducing new institutions while retaining existing ones, thereby altering the nature of the institutions in place. Drift is characterized by a situation in which institutions fail to properly adapt to changes in the surrounding environment and thus deviate from their original intents. Finally, conversion is a practice in which existing institutions are implemented in different ways while their overall frameworks remain unchanged (Table 1).

While displacement, in and of itself, is discrete, it exhibits a gradual nature within a larger institutional system. This interpretation can be likened to a situation where a capitalist market economy, once introduced in communist countries, still needs time before it affects and changes their entire social system. Drift and conversion are similar but differ in the following respects. Drift is highly likely when entities responsible for implementing institutions fail to properly respond to changes in the overall environment. In contrast, conversion refers to a practice where entities responsible for implementing institutions attempt to aggressively change how institutional rules are interpreted, thereby providing existing institutions with new functions (Mahoney & Thelen, 2010; Kim, 2023: p.335).

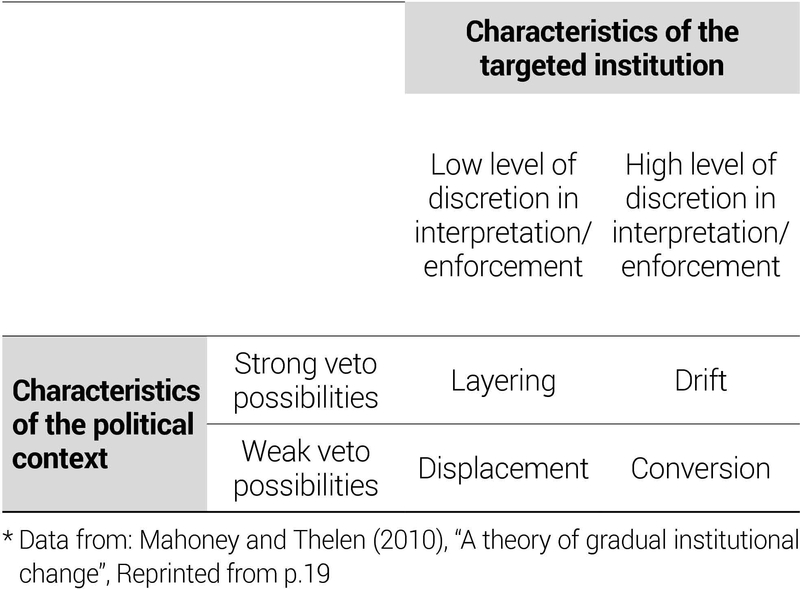

In a political environment in which there are strong veto possibilities against institutional change, institutions are less likely to undergo displacement and conversion in practice, while drift and layering are more likely. Additionally, with regard to institutional interpretation and enforcement, the type of institutional change may differ depending on the discretion of the government, which is responsible for implementing such institutions. When the government has higher discretion in interpreting and implementing its institutions, drift and conversion are more likely. However, when it has lower discretion, the likelihood of both layering and displacement increases (Table 2).

However, external impacts alone-which have been pointed to as the main drivers of institutional change in the context of historical institutionalism-cannot satisfactorily explain the gradual nature of such changes observed in reality (Ha, 2001). In response, a group of scholars have shifted their focus on ideas in attempts to conceptualize the endogenous, gradual nature of institutional change driven by actors (Blyth, 1997; Hay, 2004; Peters et al., 2005).

By their definition, ideas refer to the causal belief structure that consists of actors' cognitive and normative elements (Lee, 2023). Ideas serve to filter through a large amount of information and guide actors toward the direction they desire, thereby supplementing policy makers' limited exploratory and computational capabilities and providing insights into alternatives, strategies, legitimacy, and discourses (Lim, 2022). Furthermore, Blyth (2002) argued that ideas functioned as causal factors in the dynamic analysis of institutional change. The researcher focused on the multiple roles of ideas in reducing uncertainty during times of crisis, enabling actors to diagnose the situation, engage in group action, and form alliances; criticizing existing institutions in order to lay out a blueprint for new institutions; and coordinating actors' expectations on such new institutions, once put in place, thus facilitating their stabilization (Blyth, 2002: pp.34-45).

Ideas may represent different elements, depending on which dimension is considered, such as policy solutions, policy paradigms, and public sentiments (Schmidt, 2002; Campbell, 2002; Yoon, 2013; Ha, 2016: p.216-217). Among them, policy solutions outline specific directions for policies as policy prescriptions or measures, contributing to addressing the policy problems faced by the public sector while providing effective tools to help achieve the desired goals(Yoon, 2013; Ha, 2016: pp.216-217). Ideas may either broaden their scope across the globe or be selectively interpreted and applied to each region according to its unique history and institutional context (Ha, 2016: p.233).

2. Evolution of the Idea of Heavy Taxation on Unearned Income from Real Estate

The use of land embodies publicness as it not only affects the neighboring land from a spatial perspective but also influences the next generations that follow from a temporal perspective (Kim, 2019). In the context of classical political economy, land is characterized by immobility and limited supply, and land rent, defined as the price paid for land, is regarded as the excess of total revenue over the costs of other production elements. Furthermore, land rent is commonly regarded as unearned income as land is given by nature free of charge (Lee, 1987). In this respect, the concept of land value capture (LVC) has been actively discussed across the board, from public finances to urban planning. The LVC states that any increase in the value of private land, resulting from public-sector investment in infrastructure, changes in land usage plans, population growth, etc., needs to be viewed as unearned income and thus recaptured in the form of taxation or fees (Walters, 2013).

The OECD and the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy categorize policy instruments for LVC into five groups: infrastructure levy, developer obligations, charges for development rights, land readjustment, and strategic land management.1) The institute views that although not included in these categories, land and property tax can also serve as a policy tool for LVC to some extent (OECD/Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, PKU-Lincoln Institute Center, 2022: pp.16-17).

Among them, the idea of heavy taxation on unearned income from real estate, especially tax on land rent-those that underlie the concepts of infrastructure levy and land and property tax-as well as its evolution over time, will be discussed in more detail below. In the Wealth of Nations of 1776, Adam Smith argues that land rent can be defined as a monopoly income earned without effort by landowners (Smith, 1992: p.150), and that the burdens of taxation on such land rent cannot be shifted from one to another, and thus this type of tax needs to be viewed as a lump-sum tax (Kim, 2022).2) David Ricardo, who is often considered the first to formulate a precise theory of land rent, defines land rent as the “payment made to the landlord for the use of the original and indestructible powers of the soil among the products of the land” (Ricardo, 2010: p.73). Ricardo also proposed the differential rent theory, which explains how the difference in land quality inevitably leads to excess profit, or rent, for the landowner; population growth must be accompanied by the use of marginal land due to the law of diminishing returns, and thus rent should be paid for the use of fertile land (Ricardo, 2010: pp.76-81; Byun & Lee, 1994: p.41). Ricardo argued that the landed class's land rent income led to a decrease in the profits of the capitalist class, hindering their capital accumulation, and that taxation on land rent put all the burden on landowners as it could not be shifted to other s(Ko, 2000).

Henry George, an American economist, leveraged Ricardo's analytical tools to conclude in his book Progress and Poverty that the underlying causes behind the increasing poverty, recurring recessions, and persistent unemployment experienced by the working class despite material progress include the possession of land by a group of people as exclusive private property (Jun, 2001). In an attempt to address this problem, the economist proposed introducing taxation on land rent as a way to recapture the rent incurred from land while recognizing the proprietary rights of landowners (George, 1997: pp.389-391).

3. LEPT and CREHT, Korea’s Policy Tools of Heavy Taxation on Real Estate

The land excess-profit tax (LEPT), previously one of Korea's most stringent tax policies on unearned income from real estate, in practice, ironically applied to idle land from which no land rent income had yet been incurred as a result of land lease or sales. More specifically, LEPT states that 50% of the excess of the unrealized capital gains incurred from an increase in the price of private idle land or non-business land owned by corporations over capital expenditures and normal land price increases be taxed (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012: p.135). Rapid urbanization, coupled with landowners’ land development efforts, has led to a rise in land price regardless of its usage status, ultimately causing speculation in land purchases and undermining equity in taxation (Jung, 1994). While the capital gains tax is a transaction tax that targets the capital gains realized following the purchase and sale of land, LEPT is a holding tax on the unrealized capital gains incurred from an increase in idle land price. In this regard, LEPT is highly stringent and thus can be viewed as a tax on unearned income from land rent (Song & Choi, 1995). Since the enactment of the enabling law for the policy in 1989, LEPT had been implemented until it was determined to be unconstitutional in 1994 when its enabling law was overhauled. Later, in 1998, LEPT was finally repealed (National Tax Service, 1999: pp.149-150).

In 2005, the comprehensive real estate holding tax (CREHT), which includes heavy taxation on unearned income, was first introduced. Its enabling law aims to promote equity in taxation and stabilize real estate prices, thereby facilitating the balanced development of the national economy (Ha, 2008). By adjusting the rules under the comprehensive land tax and property tax, CREHT levies a comprehensive tax on land, houses, and buildings based on ownership; it is levied on large-scale real estate owners whose properties exceed a certain threshold to promote equity in holding taxation and stabilize real estate price (Lee et al., 2018). Its enabling law also prescribes that tax revenues from CREHT under the Local Subsidy Act may be used as funds for real estate tax redistribution, the entire amount of which is thus allowed to be allocated to local governments, therefore enhancing social equity (Ha, 2008). However, many questions and concerns were raised from the onset of its introduction; in 2008, its household aggregation rule was declared unconstitutional, and the rule on the one-household, one-home rule for long-term ownership was declared incompatible with the Constitution. CREHT is now viewed as having deviated from its original intent through such developments (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012; Kim, 2024).

4. Literature Review and Distinctive Features of This Research

Studies on land excess-profit tax (LEPT) have mainly focused on the legal discussion of the tax system and the assessment of policy impact (Lee, 1994; Han, 1998; Lee, 2009). Han (1998) criticized LEPT for levying a tax on unrealized capital gains, arguing that this attempt would force landowners to develop their land or bear unnecessary tax burdens. Lee (1994) took a negative stance against the ruling declaring LEPT incompatible with the Constitution and argued that all development gains must be completely recaptured to prevent society's wealth from being taken over by private individuals. Lee (2009) emphasized that the ruling declaring LEPT incompatible with the Constitution still recognized the legitimacy of LEPT, and thus, such taxation on unrealized gains was also still among the options available for legislators.

By analyzing the effectiveness of LEPT, Jung (1994) demonstrated that the policy contributed to curbing real estate speculation, addressing an unequal distribution of land ownership, promoting the recapture of development gains, and enhancing efficiency in the use of land. Song & Choi (1995) conducted a survey of residents across three dongs of Suseong-gu, Daegu-si on LEPT before and after the ruling declaring LEPT incompatible with the Constitution. The majority of the respondents were in favor of LEPT or supplementing its provisions. Meanwhile, Son (1994) criticized LEPT for having deviated from its original purpose, forcing land use by genuine land users. Lee & Oh (1994) considered that while LEPT had contributed to stabilizing real estate prices, it had also led to the rapid development of idle land, causing disruptions in the supply of materials and human resources.

Studies on the comprehensive real estate holding tax (CREHT) have been consistently conducted since 2003, when this issue began to be discussed (Kim, 2004; Kim, 2005; Kim, 2010; Kim, 2016; Cha, 2024). Studies conducted before its legislation include a work by Kim (2004), arguing that while LEPT and CREHT were similar in targeting unrealized gains, CREHT was rather a normal property tax in contrast to LEPT, an emergency tax designed to prevent real estate speculation. Yoo (2004) raised concerns that CREHT would not be able to achieve its desired goals because its burden could be shifted to others, failing to stabilize real estate prices as desired and possibly resulting in a regressive tax structure. Park (2005) considered that the complexity of CREHT would only add to administrative costs, proving its inefficiency. Kim (2004) argued that the adjustment of existing tax arrangements must precede the introduction of new legislation, i.e., CREHT, to maintain tax neutrality and enhance local finance.

After the passing of the CREHT Act, Kim (2005) analyzed the behavior of interested parties in favor of and against CREHT through study cases of its legislative process. Park & Kim (2005) contended that its legitimacy should be based on the need for taxation on gains from public services or imputed income rather than on the public concept of land. Park (2006) criticized CREHT for being excessively used for the purpose of stabilizing the real estate market, while Yoo (2006) pointed out that the reduction of acquisition tax and registration tax, which aimed to ease the increased burden of hold taxation due to CREHT, could lead to a decrease in local tax revenues. Kim (2007) emphasized the need to repeal CREHT, attributing the policy to causing tax resistance and division among people. Jung et al. (2008) highlighted that the household aggregation rule of CREHT violated the principle of equity, and its high-rate progressive taxation infringed upon the original nature of the tax itself and was thus highly likely to be declared unconstitutional.

After the ruling declaring CREHT unconstitutional, Kim (2010) took CREHT as an example of a tax policy that was intentionally designed to be resistant to change, explaining relevant institutional changes by pointing out both positive feedback (establishing coexistence funds for local communities in response to reduced local allocation tax) and negative feedback (tax resistance among affected groups) inherent in CREHT. Likewise, over the period from the Roh Moo-hyun administration's introduction of CREHT to the ruling declaring it unconstitutional, extensive research has been actively conducted on its legal implications and effectiveness.

Kim (2016) examined the entire course of CREHT's introduction and collapse, focusing on changes in the public opinion management strategies of those who had promoted its implementation. According to the study, in 2003, around the time of the introduction of CREHT, public opinion was generally supportive of the tax policy. However, in 2005, the authorities began to strengthen taxation as the country's real estate market was on the rise, thereby extending the scope of potential taxpayers to include even the middle class. This served as an important milestone where public opinion about CREHT shifted from being positive to negative.

Later, Oh (2018) and Kim (2020) argued for converting CREHT into a local tax and integrating it with the property tax. Kim (2018) and Han & Kim (2021) examined double taxation adjustment regulations for CREHT and property tax. Meanwhile, many research groups, including Noh & Shin (2021), Lee & Song (2021), Seo & Park (2022), Ha & Song (2023), Lee et al. (2023), and Jung & Sung (2024), analyzed the effect of changes in CREHT on housing prices. Lim et al. (2022) and Cha (2024) studied heavy taxation through CREHT targeting multiple homeowners.

Most studies on LEPT and CREHT have mainly focused on their legal implications and effectiveness. However, tax policies are formed and evolve in the context of not only legal and economic aspects but also historical and political perspectives. Apart from studies by Kim (2010) and Kim (2016), few studies have covered a wide range of such contexts in a comprehensive manner.

Primeval institutional ideas tend to evolve differently depending on the country and its historical and political circumstances. These ideas then compete against one another, and in the process, the respective interests of actors engaging in policy-making are considered. Finally, only the selected ideas are reflected in institutional change. Additionally, tax policies encompass not only economic aspects but also political considerations as redistribution measures, and thus, their legal stability can be achieved through gradual changes (Jung, 2009; Kim, 2018).

This study differs from others in that the idea of heavy taxation on unearned income from real estate, which underlies the basis of both LEPT and CREHT, is explored based on the theory of gradual institutional change. The main focus will be on how this idea was first introduced and has survived today, as well as how policy frameworks that embody the idea have been implemented and adjusted based on their respective contexts. To the best of the knowledge of the current authors, no studies on LEPT and CREHT have taken this approach so far.

III. Research Methods

1. Scope of Research and Materials Analyzed

The temporal scope of this research encompasses the period from the Roh Tae-woo administration to the Yoon Seok-yul administration. This research explores how each government's tax policies and relevant policy ideas have evolved over a long period of time and also how the government as a policy provider and the general public as the policy recipients have interacted with each other, as well as how these developments and interactions have affected the country's institutional change. The analysis was performed on the land excess-profit tax (LEPT) and the comprehensive real estate holding tax (CREHT), which were deemed to be built on the idea of heavy taxation on unearned income from real estate. The rationale behind this selection was that in contrast to the capital gains tax, which targets realized capital gains, both tax policies intended to recapture unrealized gains (Park & Shin, 2020) and thus caused tax resistance while also being declared incompatible with the Constitution by the Constitutional Court (Lee, 2009; Moon, 2009), in addition to the expectation that it would be possible to analyze not only the tax policies themselves but also gradual changes in the idea underlying them.

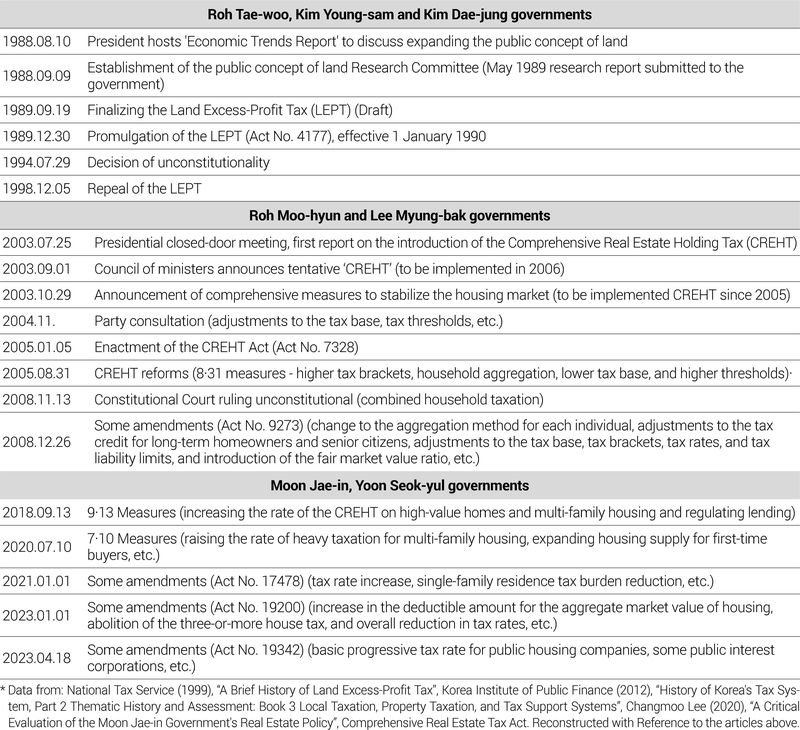

After being introduced by the Roh Tae-woo administration, LEPT was put in place over the period from 1989 to 1994. It was later declared incompatible with the Constitution under the Kim Young-sam administration and was then weakened to a lesser form. In 1998, it was finally repealed by the Kim Dae-jung administration during the IMF financial crisis. Afterward, the Roh Moo-hyun administration formulated CREHT by allowing it to inherit the roles of both comprehensive land tax and property tax while enhancing their heavy taxation on unearned income. CREHT was then put in place amidst a range of controversies until it was subjected to a significant change as the Constitutional Court declared the policy unconstitutional under the Lee Myung-bak administration. With the inauguration of the Moon Jae-In administration, CREHT strengthened again, but it was then subjected to another significant change as the power shifted to the Yoon Seok-yul administration (Table 3).

Literature, newspaper articles, press releases, and National Assembly records regarding changes in both LEPT and CREHT were analyzed, with a particular focus on newspaper articles detailing the process of policy change.

2. Analytical Framework

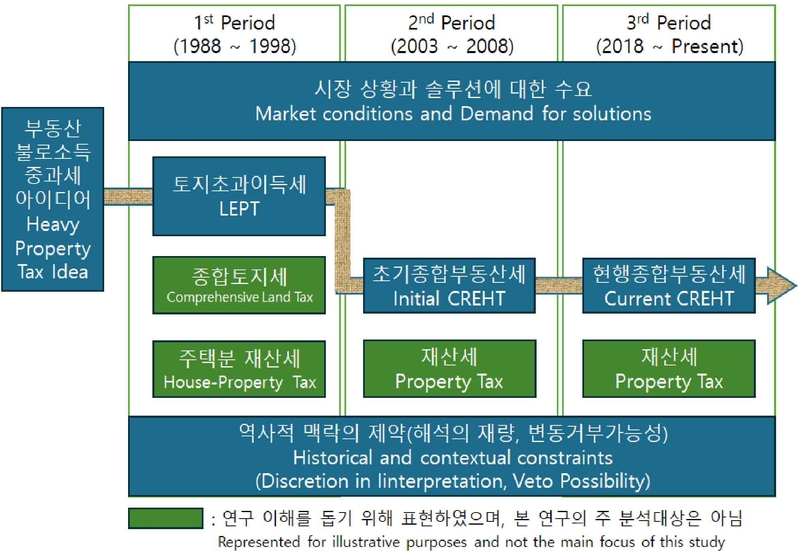

The analytical framework of this study provides insights into how the idea of unearned income from real estate has been extended to encompass the public concept of land in the form of taxation on land rent income; specifically, the idea of taxation on land rent income evolved into LEPT under the Roh Tae-woo administration, and further into CREHT during the Roh Moo-hyun administration and its successors.

The first period spans from 1988 to 1998, encompassing Roh Tae-woo administration's adoption of the primeval idea of heavy taxation on land rent income and formulation of LEPT, the Constitutional Court's ruling declaring LEPT incompatible with the Constitution, and the repeal of LEPT in 1998. In the context of policy formulation, the realization of the idea, the possibility of vetoes against change, resistance against the policy from taxpayers, and the Constitutional Court's rationale for the ruling of unconstitutionality all are expected to form a single path.

The second period encompasses the Roh Moo-hyun administration's discussion on CREHT in 2003, its adoption in 2005, resistance from taxpayers, the Constitutional Court's ruling of unconstitutionality in 2008, and the incapacitation of the policy. It was deemed that the historical context of the first period constrained the second period's government decision-making in a path-dependent manner, affecting how the policy evolved. The third period spans from the Moon Jae-in administration's strengthening of CREHT in 2018 to its weakening, followed by a discussion of its repeal during the Yoon Seok-yul administration. The second period's historical context was also considered to affect the third period's government decision-making, in turn influencing the evolution of the policy.

The main drivers of these changes include the government's exploration of solutions and the features of ideas used in the process. The growing need for government intervention in the real estate market, which recurred over time, was naturally linked to the idea of heavy taxation on unearned income, proposed as a solution.

In contrast, the constraints stemming from historical contexts were analyzed according to the theory of gradual institutional change in terms of displacement, layering, drift, and conversion. Discretion in interpretation and execution in the adoption and implementation of the policy, as well as the possibility of vetoes exercised by relevant stakeholders against institutional change, were analyzed (Figure 1).

Ⅳ. Changes in the Policy of Heavy Taxation on Unearned Income from Real Estate

1. First period: Adoption, Formulation, and Repeal of LEPT

An increase in demand for land following industrialization in the 1960s led to a chronic imbalance between land supply and demand. As real estate speculation spread throughout the country, fueled by the 1988 Seoul Olympics, land prices surged, and the imbalance of land ownership intensified (National Tax Service, 1999: p.7). The inflow of foreign exchange, resulting from the country's current account surplus, added to the pressure for an increase in currency supply. In the second half of 1988, as the economy picked up, inflation was expected to rise, directing capital into real estate as safe assets. This was another reason behind the land price surge (Lee, 1999: p.209). As the national income increased by 2.9-fold from 1975 to 1988, the land price rose by as much as 8.4-fold. The imbalance in land ownership also deepened, with the top 5% of the population possessing 65.2% of the land (National Tax Service, 1999: p.7).

In the late 1970s, Hyong-sik Shin, Minister of Construction, explicitly proposed the public concept of land as the "fundamental ideology of new public welfare-oriented land policies, emphasizing that limited national land resources must be used properly and effectively to promote the prosperity of the public" (Park et al., 1998). Although there were existing policies based on the public concept of land, such as the land transaction reporting system, excessive holding tax, and the regulation system for land transactions, their effectiveness was questioned. Back then, public opinion was also highly supportive of enhancing and introducing the public concept of land as a fundamental solution to prevent real estate speculation with the recognition of its severity. In response, the policy community, including the Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements, began broadening the consensus within it regarding the expansion of the public concept of land (Lee, 1988). Given the severity of real estate speculation, even conservative media outlets called for the introduction of the public concept of land with conviction, proposing the implementation of the idea of a land value tax (single tax) advocated by Henry George (Jang, 1988).

The fact that "65.2% of the private land was owned by the top 5% landowners" was revealed by analyzing the electronic land records of the Ministry of Home Affairs for the first time in history, which highlighted the imbalance in land ownership (National Tax Service, 1999: p.9). Even within the Ministry of Home Affairs, many argued against disclosing such data representing land ownership being excessively concentrated among certain social classes as this might lead to political risks, e.g., a reduction in the support base. However, Hi-gab Moon, Senior Secretary for Economic Affairs to the President, and Seung Park, Minister of Construction, strongly urged to make it available to the public. Despite fierce opposition from the Democratic Justice Party as the ruling party, this disclosure played a critical role in directing public opinion in favor of the public concept of land (Lee, 1999: pp.225-227).

The government's August 10 Measures in 1988 served as a key milestone in turning the idea of the public concept of land into reality. In fact, the Roh Tae-woo administration came into existence following the June Struggle for Democracy and democratization in 1987 and was thus confronted with an urgent need for a complete break with its predecessor because Roh Tae-woo himself had served as the key member of the new military regime before the transition to democracy. Therefore, the administration had every reason to respond to the demands of everyday citizens in industrial sites and living environments and further strengthen its support base. In the late 1980s, as the 3-low economic boom resulted in a real estate speculation frenzy, the need for reform became more urgent (Kim, 2012). In August 1988, President Roh Tae-woo hosted the economic trends report meeting himself, and as a result, a comprehensive real estate policy titled the August 10 Measures was formulated, which served as a venue for discussion on the introduction of the public concept of land (Lee, 1999: p.204).

Through the August 10 Measures, the government aimed to recapture all development gains to ensure that land was owned by those who sought to use it, thereby eliminating the root cause of land speculation. In September 1988, the Land Public Concept Research Committee was organized to devise institutional measures, such as a land ownership ceiling and comprehensive land tax. There was a fierce debate on this very issue, followed by relevant activities. For example, a public forum was held by the Land Public Concept Research Committee. The opinions were divided on the introduction of the public concept of land. National Assembly members and the Federation of Korean Industries argued against the concept, emphasizing the importance of the efficient use of national land. In contrast, scholars, journalists, and private organizations advocated for the acceptance of the concept, pointing to the need to regulate land ownership (Lee, 1989).

Although LEPT was newly established, its formulation could be considered through conversion as existing relevant policies were not eliminated. The ideas of both the public concept of land and taxation on land rent were strongly reflected in LEPT, significantly improving the limitations of existing policies. Additionally, given the political and societal situation, the likelihood of vetoes was minimal.

In May 1989, the Land Public Concept Research Committee submitted its research report, which proposed introducing development charges and the recapture of development gains, i.e., LEPT. Imposing development charges was aimed at recapturing any development gains incurred from land development projects, land use change projects, etc., in the form of a utility bill. The recovery of development gains was aimed at absorbing the excess profits from an increase in the value of idle land and vacant land in areas where land prices rose beyond the normal rate (Lee, 1999: p.215; National Tax Service, 1999: pp.11-12). In this report, the committee defined development gains as unearned income, i.e., money that landowners received without actually working, as pointed out by David Ricardo through the theory of rent. Given that land supply fell short of demand for develop ment due to limited land resources, resulting in excessive land price increases, they advocated for the social recapture of development profits (Land Public Concept Research Committee, 1989: p.180).

The public was generally supportive of this law at the time when the introduction of LEPT was considered. Voices were raised from all sectors of society, demanding distributive justice, more equity, and balanced development. Based on the widespread consensus that the surge in land prices was attributed to prevalent land speculation, the vast majority of the public supported the introduction of three acts based on the public concept of land (Kim et al., 1989). A national survey conducted by the Economic Planning Board on the public concept of land showed that 72.2% of the respondents pointed out the seriousness of land and housing issues, and 88.6% argued for more stringent regulations on real estate speculation. The middle class or the white-collar class was more supportive of the concept, and the vast majority of the respondents viewed land system reform also as the prerequisite to advancing democracy in the country (Park, 1989).

LEPT was finally implemented on January 1, 1990. In June 1989, it was determined that development gains would be recaptured in the form of a prepayment of the capital gains tax. The Senior Secretary to the President for Economic Policy hosted a meeting and discussed real estate policies and relevant strategies for introducing the public concept of land. The agendas of the meeting included the strengthening of real estate taxation (establishing comprehensive land tax, adjusting the tax base to reflect market value, strengthening the capital gains tax, etc.); the establishment of a transaction order (expanding both the land transaction reporting system and the regulation system for land transactions, requiring the use of approval seals in contracts, etc.); supply of housing and low-cost housing sites (constructing new towns, 2 million houses, 250,000 permanent rental houses, etc.); and the introduction of the public concept of land (introducing land ownership ceiling, the recapture of development gains, etc.). Following policy coordination between relevant government agencies in July, the "Land Excess-profit Tax for Development Gains Restitution Act" was pre-announced for legislation on August 26. The Act's title was changed to the "Land Excess-profit Tax Act" in September, and it was then resolved at the National Assembly plenary session on December 18 before being promulgated on December 30 (National Tax Service, 1999: pp.12-15).

Once the tax was imposed, resistance emerged. The key challenge was the uncertainty inherent in the tax criteria of LEPT, raising strong complaints from taxpayers. Multiple revisions were made to the Act, but to no avail. This challenge stemmed from the fundamental limitation of LEPT, i.e., the difficulty in estimating unrealized profits in an objective manner. Later, LEPT was declared incompatible with the Constitution. This ruling, combined with the transformative socioeconomic changes resulting from the IMF financial crisis, eventually led to the repeal of the policy.

Since the implementation of the Act, the National Tax Service had imposed the tax on a total of 99,000 people, totaling 1,080 billion won, through planned taxations in 1991 and 1992 and regular taxation in 1993 (Jin, 1994). However, the Enforcement Decree of the Land Excess-profit Tax Act was enacted in December 1989, and the Enforcement Rule of the Act was implemented in March of the following year. The act was revised in December 1994, the Enforcement Decree was revised a total of seven times, and the Enforcement Rule was revised five times. The planned taxation conducted in 1991 and 1992, as well as the regular taxation in 1993, revealed that there was much room for improvement. By reflecting the complaints raised, the Act and relevant rules and regulations were subjected to revisions (National Tax Service, 1999: pp.31-44).

While LEPT aimed to recapture the potential development gains that might occur in land near development project sites, it was highly challenging to determine the spatial effect of various development activities on the neighboring land parcels. The authorities then decided to adopt the normal land price increase rate (whichever is higher between the mean rate of national land price increase and the interest on fixed deposits) as a benchmark. If the land price increase was beyond this threshold, the corresponding profits were deemed excess. Additionally, in an effort to curb tax resistance, only the idle land that fulfilled specific requirements was taxed, and those owned by actual land users were excluded from taxation (Son, 1994).

However, the lack of a reliable land price estimation system led to unexpected estimation errors. What made matters worse was their passive response to the demands of taxpayers to re-estimate the appraised value of their land. Moreover, as the number of criteria for determining whether land was idle under the Act was limited, some decisions were made in a less informed manner, categorizing certain cases as taxable even though there were no signs of speculation based on social norms. If there were discrepancies between the records and reality, local taxation offices often determined that the records prevailed, and they conducted taxation accordingly due to their limited administrative capacity. Furthermore, the types of land subject to LEPT, such as raw land, agricultural land, and forests, were mostly located in remote areas or rural regions rather than in urban areas. This meant that many farmers and low- and middle-income residents were taxed, triggering fierce resistance from them. A high degree of discretion in execution, combined with discrepancies with reality, was deemed to have led to extensive complaints, causing the policy to drift (National Tax Service, 1999: pp.102-103).

Confronted with strong tax resistance, the Democratic Liberal Party organized the Investigation Committee for the Current Status of LEPT Taxation. The committee conducted a field survey for seven days, starting July 1993, and submitted its investigation report. Based on the content of the report, the Enforcement Decree of the Act was revised in August 1993. The report pointed out that the limitation of LEPT was its targeting of unrealized profits, as it could be deemed unconstitutional, and that if land prices decreased, the tax collected must be returned. There was also a risk that landowners might consider building unnecessary structures only to evade taxation, distorting the efficient allocation of resources. According to the report, the minimum area of land attached to houses to be exempt from the tax was 80 pyeong (264.5 m2) for rural areas and 60 pyeong (198.3 m2) for metropolitan cities and directly governed cities, which were deemed a relatively low threshold from a realistic perspective. The report emphasized that classifying even the land attached to unauthorized buildings and structures as idle land meant extending the scope of taxation to include farmers as well as everyday citizens (Ko & Jung, 1993).

Complaints continued, and many appealed against the tax authorities' decisions regarding LEPT. An increasing number of cases were decided against the government. On July 29, 1994, major revisions were made to the Act and relevant rules and regulations, including the provisions declared incompatible with the Constitution and even those that comprised the fundamental framework of the Act (National Tax Service, 1999: p.124). Upon the ruling declaring LEPT incompatible with the Constitution, the National Tax Service developed a separate guidance for taxation, ensuring that LEPT was no longer newly imposed under the current version of the Act (Jin, 1994).

Regarding the Constitutional Court's ruling, taxation on unrealized profits was declared constitutional as this issue was subject to tax policy decisions. However, regarding the tax base, determining the standard market price through the Presidential Degree was deemed to violate the principle of no taxation without law under the Constitution; however, given that most tax laws delegated such tasks to enforcement decrees, the court demanded the revision of the relevant provisions instead of declaring them unconstitutional. Moreover, levying the tax on long-term landowners for specific taxable periods was deemed to violate their right to private property because no actual excess profits occurred due to an increase or decrease in land prices, possibly resulting in unreasonable consequences. High-rate taxation on unrealized profits, in particular, involved the risk of violating the right to property. Additionally, applying a flat tax rate was deemed to undermine substantive equality as it was levied in the form of a prepayment of the capital gains tax (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012: pp.141-143; National Tax Service, 1999: pp.124-126).

The IMF financial crisis in late 1997 was followed by a downturn in the real estate market. Land prices thus stabilized, and additional policy tools were introduced; there was no room for LEPT. It was finally repealed in 1998. Before its repeal, the effectiveness of LEPT was significantly questioned, and voices were raised against the policy. In December 1997, as real estate prices plummeted as a result of President Kim Dae-jung's pledge for neoliberal tax reform, coupled with the financial crisis, the authorities actively considered repealing the acts related to the public concept of land. Later, in March 1998, members of the National Assembly, including Oh-yeon Na (Hannara Party), submitted to the National Assembly a bill to repeal the Act through legislation jointly by lawmakers and the Ministry of Finance and Economy. On December 28, 1998, LEPT was officially repealed (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012: pp.140-141). Besides the Constitution Court's ruling, the introduction of supplementary policy tools to prevent real estate speculation, including the registration of real estate under the actual titleholder's name and the comprehensive land information system, combined with stabilized land prices resulting from the aftermath of the IMF financial crisis, made it no longer necessary to retain LEPT (National Assembly Secretariat, 1998).

2. Second Period: Adoption and Formulation of CREHT and Its Incapacitation

As the IMF financial crisis subsided, the economy began to gradually pick up. In 2001, signs of overheating were detected in the real estate market, especially centered around the Gangnam district and the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Concerns were raised, and the introduction of stringent tax policies to regulate land ownership was discussed and considered again to address real estate speculation. The national housing prices rose by 11.2% from July 2001 to September 2003. Within the year 2002, in particular, the price of apartment complexes nationwide surged by as much as 22.8%. Starting in the latter half of the Kim Dae-jung administration, the real estate market began to soar. Therefore, the Roh Moo-hyun administration had no other choice but to concentrate its resources on stabilizing the country's housing market throughout its entire period (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012: p.33; Lee, 2017).

In fact, the Roh Moo-hyun administration had come into existence based on political support from non-homeowner residents suffering from housing price spikes. Therefore, to the administration, the issue of real estate was a critical political agenda that it could not ignore if it were to attract social support (Kim, 2014). In an effort to express its firm commitment to this cause, President Roh Moo-hyun publicly proclaimed that “The government will risk everything it has to address real estate speculation, which causes more harm to the ordinary citizens of our country.” Affected by Jung-woo Lee, Chairperson of the Presidential Commission on Policy Planning, who was an advocate of taxation on land rent, President Roh was supportive of strengthening holding tax and attributed the instability of the housing market to speculative demand (Kim, 2014; Lee, 2005).

It had already been 10 years since Jung-woo Lee began his research on real estate issues by organizing a research society dedicated to Henry George's theories. Some of the research society's scholar members provided ideas regarding taxation on land rent through presidential meetings at Cheongwadae, the Korean presidential residence. Back then, expert meetings were organized at the direction of President Roh, and through these meetings, the October 29 Comprehensive Measures were drafted, which later led to the formulation of CREHT (Lee, 2024: pp.336-340; Goo, 2024). The Roh Moo-hyun administration advocated for the public concept of real estate, which combined the public concept of land underlying LEPT with the public concept of housing. The administration organized a review committee for the public concept of real estate and extended its regulations on real estate to include housing regulations as well, such as the recapture of reconstruction gains and the regulation system for housing transactions (Park & Lee, 2009; Kim, 2011). Meanwhile, the academic community argued that real estate-related tax systems should be reorganized to strengthen property tax and weaken transaction tax. This argument also played a critical role in the introduction of CREHT (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012 (Volume 2): pp.160-161; Lee, 2010: p.285).

In fact, even before the introduction of the comprehensive land tax, there were policies whose nominal functions were to tax excessive real estate holdings, such as excessive land holding tax and property tax. However, both tax policies were limited; the property tax was levied at a flat tax rate, and for the excessive land holding tax, the tax base was limited and the tax rate was low, which resulted in limited effectiveness. To overcome these limitations, the property tax and excessive land holding tax were integrated, and all land holdings across the country were aggregated for each individual owner. As a result, the comprehensive land tax was established as a local tax. The progressive tax rate applied, and individual-based aggregate taxation was adopted (Lee, 1999: pp.411-413).

However, both property tax and comprehensive land tax were less effective in preventing excessive real estate holdings due to the low holding tax and high transaction tax rates. It was also difficult to adjust the tax base for them to reflect market value. In addition, the discrepancy of the tax base relative to market value significantly varied depending on the region or property type. The lack of effort by the heads of local governments to align the tax base with reality was combined with the excessive use of flexible tax rates. Moreover, the comprehensive land tax as a local tax was insufficient for the aggregation of land holdings across the country. (Lim, 2009).

The introduction of CREHT could also be considered through conversion. Instead of reviving LEPT, which had already proven problematic in many ways and had even been declared incompatible with the Constitution, the government endeavored to restore the function of heavy taxation on unearned income from real estate while retaining the functions of the existing comprehensive land tax through CREHT, which was also equipped with an enhanced property tax. The comprehensive land tax was established at the time of the introduction of LEPT. Due to the low tax amount, its influence was minimal, resulting in almost no tax resistance. Given the social climate at the time, the likelihood of vetoes against the revival of heavy taxation on real estate was also low. CREHT was a sort of wealth tax imposed at progressive rates on the properties of individuals with excessive real estate holdings (Kim, 2016). CREHT, which broadened the taxable scope of the comprehensive land tax to include houses, was first proposed through the September 1 Measures, which was announced in September 2003. Doo-kwan Kim, Minister of the Government Administration and Home Affairs, announced a reform plan for real estate holding tax, in which the establishment of CREHT was outlined to promote equity in property taxation and prevent real estate speculation (Lee, 2003).

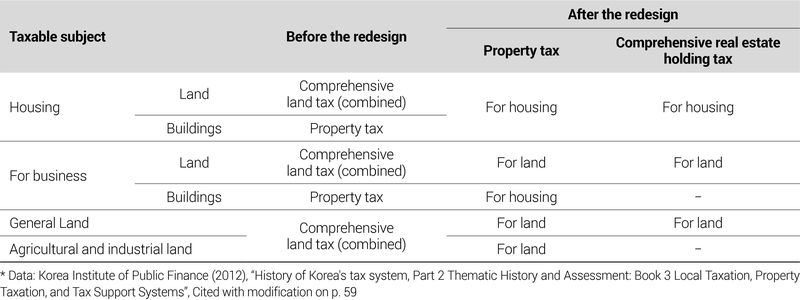

The surge in apartment complex prices, starting in the Gangnam area, extended across the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Confronted with growing instability in the real estate market, the government announced the October 29 Comprehensive Measures, which encompassed tax systems, financing, and housing supply. Accordingly, it was decided that heavy capital gains taxation on households owning three homes and the housing transaction reporting system would be introduced, and CREHT would be implemented in 2005: one year earlier than originally planned. A real estate taxation working group was then established under the Ministry of Economy and Finance to develop detailed execution plans. Under the existing evaluation system, houses were assessed by dividing them into the building and the land attached to it, even though housing was commonly traded as a unit that included both land and buildings. To reduce complexity and make this practice align with the common sense of the public, it was decided that the evaluation and taxation of housing would be conducted on a housing unit base3) (Table 4) (Kang et al., 2018: pp.275-276).

In the course of this discussion, Jung-woo Lee, Chairperson of the Presidential Commission on Policy Planning, argued that separately taxing land and buildings would be more desirable from a tax theory perspective. The rationale behind his argument was the idea of taxation on land rent; he considered that while land as a natural resource should be heavily taxed, buildings as products of human labor should be lightly taxed. However, over the formulation process of CREHT through conversion, the concept of taxation on land rent inherent in LEPT was diluted, and, instead, a shift occurred toward imposing heavy taxation on the entire tax base of both land and buildings. This shift was prompted by reflection on real estate transaction practices and the public's common sense, as well as efforts to overcome the limitations of existing property tax and comprehensive land tax (Shin, 2004).

Following the implementation of the October 29 Comprehensive Measures in 2003, housing prices stabilized. In August 2004, however, President Roh Moo-hyun established the real estate policy working group and the practical planning task force through the National Economic Advisory Council’s first real estate policy meeting to develop reform plans for the holding tax. It was decided that from 2005, land and buildings would be evaluated and taxed together as a single unit in housing assessments, CREHT as a national tax would be implemented, the process of adjusting the tax base to reflect market value would be accelerated, and a system to monitor actual transaction prices would be developed (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012: pp.174-175).

The Roh Tae-woo administration and the Kim Youngsam administration aligned the tax base with reality by increasing the tax assessment ratio relative to the published price. However, the Roh Moo-hyun administration attempted to do so by increasing both the tax assessment ratio and the ratio of the published price relative to the market price. The administration determined that the published price did not accurately mirror the market price. Therefore, the administration raised the tax assessment ratio relative to the published price to 33.3% in 2002, 36.1% in 2003, and 39.1% in 2004. During the holding tax reform in 2005, the ratio was increased to 50%, and it was also stipulated in the Act that it would reach 100% by 2009 from a long-term perspective. The ratio of the published price relative to the market price was also gradually increased to 67% in 2003, 76% in 2004, and 91% in 2005 (Jun, 2019: pp.137-138).

This bill was proposed by the government and then submitted to the National Assembly through government-party meetings. Through this process, however, the taxable scope of CREHT was narrowed compared to the original proposal. The minimum threshold for housing subject to taxation was adjusted from 600 million won to 900 million won, and its tax rates were set to 1-3% for housing, 1-4% for aggregate land, and 0.6-1.6% for separate land. The maximum year-on-year tax rate increase was adjusted from 100% to 50%, but the property tax rates for housing were significantly reduced as land and buildings were taxed together as a single unit. Later, on January 1, 2005, the Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax Act (bill) was passed at the National Assembly and then implemented in five days (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012: pp.176-177).

In summary, previously, both the property tax levied on buildings and the comprehensive land tax levied on land had been taxed as local taxes, but with the enaction of the Act, the comprehensive land tax was integrated into the property tax, and CREHT began to be levied as a national tax on individuals whose combined housing and land holdings exceeded a certain value (Table 4). In accordance with these reforms to real estate holding taxation, it was decided that the total tax revenue from CREHT was distributed to local governments in the form of real estate tax redistribution to compensate for the decrease in local government finances and promote fiscal equity (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012: p.48).

With the introduction of CREHT, the real estate market declined until it shifted to an upward trend in early and mid-2005. In response, curbing the rise in real estate prices emerged as the primary agenda of the government. To this end, the government announced the August 31 Measures, which included an enhanced CREHT. These measures aimed to restore the housing tax threshold from 900 million won to 600 million won (from 600 million won to 300 million won for raw land), raise the maximum year-on-year tax rate increase from 50% to 200%, adjust the tax assessment ratio from 50% to 100% by 2009, and shift from individual-based taxation to household-based aggregation (Kim, 2016; Jun, 2019: p.141).

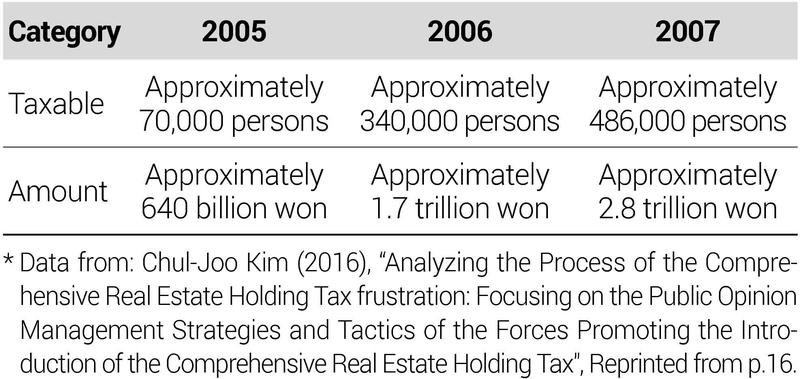

The challenge, however, was that as the real estate market experienced an upward trend from 2005 to 2007, the number of individuals subject to CREHT continued to increase. The number of CREHT taxpayers surged from approximately 70,000 in 2005 to around 500,000 in 2007. This reality was far from CREHT's original purpose of taxing individuals with excessive real estate holdings; the policy began to drift (Table 5)(Lee et al., 2008: pp.46-47). Despite the government's effort to highlight the critical role of CREHT in curbing real estate speculation, the media, especially conservative media outlets, began positioning themselves against the government by describing CREHT as a tax bomb targeted on the middle class and everyday citizens or punitive taxation. The strong public support at the time of its introduction reversed, resulting in a surge in tax resistance (Kim, 2016).

The rise in tax resistance, starting in the Gangnam area, spread across Mokdong, Gwacheon, and Bundang, followed by numerous protest rallies and petitions for legal reforms. In response, the Uri Party, as the ruling party, warned that “Denial of CREHT is an antisocial act and will face public resistance” (Jang & Kim, 2006; Kang, 2006). However, within political circles, serious concerns were raised about the surge in published property prices and the increased number of taxable entities. Some called for a relaxation of CREHT. In the lead-up to the 17th presidential election in 2007, both the Grand Unified Democratic New Party and the Hannara Party pledged to ease CREHT as part of their campaign. In December, President-elect Lee Myung-bak declared his commitment to reassessing CREHT's tax base criteria and taking measures to ease the tax burden of long-term homeowners with one property per household (Kim, 2016).

In addition to these circumstances, CREHT's household-based taxation was declared unconstitutional in November 2008, inflicting a significant setback on the tax policy (Kim, 2016). The Constitutional Court ruled that household-based taxation for housing and aggregate land was unjust tax-related discrimination for households and thus violated Paragraph 1 of Article 36 of the Constitution. The rationale was that such taxation was contrary to the intent of the Constitutional Court’s previous ruling that aggregation of income from assets in accordance with Paragraph 1 of Article 61 of the former Income Tax Act was unconstitutional. As such, the ruling declared that the intent of CREHT itself was constitutional, but its household-based taxation was unconstitutional, and taxing long-term homeowners with one property for residential purposes was incompatible with the Constitution (Lim, 2009).

Besides the Constitutional Court's ruling, the sharp rise in tax burden in the aftermath of the August 31 Measures in 2005, coupled with the global financial crisis in 2007, led to a partial revision of CREHT in a more lenient direction in December 2008. As a result, CREHT's heavy taxation function was essentially incapacitated (Korea Institute of Public Finance, 2012: p.190). Household-based aggregation was restored to individual-based taxation, and the housing tax threshold was adjusted to 900 million won for homeowners with one property in their name only. The threshold for the publicized prices subject to aggregate and separation land taxation was increased to 500 million won and 8 billion won, respectively. Additionally, a tax credit system was newly established to adjust taxation depending on the age and holding period of homeowners with one property per household. The tax rates and brackets for housing were adjusted from four tiers (1-3%) to five tiers (0.5-2%), and the overall tax rates for land were adjusted downward. Additionally, the maximum year-on-year tax rate increase was reduced from 300% to 150% (Park, 2011).

CREHT differed from LEPT in that it was not essentially repealed but retained as a tax policy in a stable manner with adjustments made flexibly to its tax criteria. More specifically, the two policies were similar in that both allowed for a high degree of discretion in interpretation and execution and were formulated through conversion due to the low likelihood of vetoes against institutional change. However, in contrast to the case of LEPT, in which strong tax resistance and the Constitutional Court's ruling resulted in the overall suspension of taxation, CREHT could ease tax resistance and remain stable through layering. However, it is worth nothing that as a consequence of this layering process, the idea of taxation on land rent inherent in CREHT was significantly diluted.

3. Third Period: Repeated Cycles of Conversion and Layering in CREHT

Following the Constitutional Court's ruling declaring CREHT unconstitutional in 2008, the issue of CREHT's heavy taxation function faded into the background for more than 10 years until the Moon Jae-in administration revisited the idea in 2018. In late 2018, as the rise in housing prices, starting in Seoul, began to spread to neighboring areas, the Moon Jae-in administration announced housing market stabilization measures, which aimed to strengthen CREHT’s heavy taxation function and loan regulations (Song & Kwon, 2020). The measures also focused on raising tax rates for high-priced housing, imposing an additional tax on both individuals owning three or more homes and those with two homes located in high-speculation areas, and adjusting the maximum year-on-year tax rate increase from 150% to 300%. Additionally, it was decided that those who acquired housing or registered rental housing in high-speculation areas would be subjected to CREHT, and that the fair market value ratio would be further adjusted upward (from 80% to 100% with an annual increment of 5%p), gradually aligning the published prices with reality (relevant government agencies, 2018). Following the partial revision of CREHT in 2019, reflecting the aforementioned adjustments, Seoul's housing prices appeared to decline before they underwent a dramatic shift toward a sharp upward trend. In response, the government announced supplementary measures for housing market stabilization in July 2020, even further increasing CREHT’s heavy taxation rates for individ uals with multiple homes (relevant government agencies, 2020). As a result, revenue from housing-related CREHT sharply rose from approximately 1 trillion won in 2019 to 4.4 trillion won in 2021 (Lee, 2023).

However, in opposition to these real estate measures, tax resistance emerged and then spread through online platforms such as Internet cafes, the National Petition to the Blue House portal, and offline protests, leading to even collective actions (Park, 2020). Following the ruling party’s landslide defeat in the by-election in April 2021, the mood shifted toward easing the tax burden of individuals with a single home for non-speculative purposes. Given that the original intent of CREHT was to tax individuals with multiple homes, possibly for speculative purposes, and the tax threshold based on the published prices for individuals with a single home consistently remained at 900 million won since 2009, the argument that the threshold should be adjusted upward in line with the rise in housing prices began to gain momentum (Choi, 2021).

Upon the inauguration of the Yoon Seok-yul administration in May 2022, the assessed amount of CREHT returned to the levels before 2019. The administration shifted toward easing CREHT, announcing tax reform measures to eliminate heavy taxation on individuals with multiple homes, reduce its tax rates, reduce the tax burden cap, and increase the basic deduction amount (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2022). The New Politics Alliance for Democracy, an opposition party, decided to oppose the passage of the reform proposal, but tax resistance intensified over time; administrative appeals were collectively filed with the Tax Tribunal in opposition to the sharp rise in tax burden (Kim & Lee, 2022). Therefore, the ruling and opposition parties agreed on the new government's reform proposal, in which only the taxation imposed on individuals with three or more homes beyond a tax base of 1.2 billion won was retained. The proposal was passed at the National Assembly plenary session in December 2022, and as a result, a partial revision was made to CREHT (relevant government agencies, 2020; Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2022). The fair market value ratio was also adjusted to its lower limit at 60% (Kwon, 2023), but a sharp decline in apartment complexes' published prices was followed, driving the tax amount abruptly down to the 2020 level (Cho, 2023). In February of the following year, the government also established a tax reform task force to further reduce the burden of CREHT and the inheritance tax (Ban, 2023).

Starting in May 2024, further discussion continued on the exemption of individuals with a single home from CREHT and even the repeal of CREHT itself (Kim, 2024). Demands for repealing or easing CREHT came not only from the People Power Party, the conservative party in power, but also from the New Politics Alliance for Democracy as an opposition party. Their rationale was that despite being in place for 20 years, it had not achieved the desired results (Son, 2024). The ruling party welcomed this response and proposed a complete overhaul of the tax system within the 22nd National Assembly (Kim, 2024). However, the party took a cautious stance on the repeal of CREHT due to concerns over a sharp decrease in tax revenue (Bin, 2024). On the other hand, the Executive Office of the President expressed its stance that it would consider the complete repeal of CREHT beyond the opposition party’s proposal of exempting individuals with a single home from taxation (Kim, 2024). Coincidentally, the Constitutional Court declared CREHT constitutional, fueling debate over the tax policy.

In June 2024, the Ministry of Economy and Finance began considering the repeal of heavy taxation levied on individuals with multiple homes, regarding it as punitive taxation. Previously, in 2022, heavy taxation on individuals with two homes had already been repealed, and the ministry further sought to exempt those with three or more homes from heavy taxation (Lee, 2024). Additionally, the administration considered switching the tax criteria from the number of houses to their value (Cho, 2024a). However, the repeal of heavy taxation on individuals with two homes had already resulted in a sharp decrease in the number of individuals subject to heavy taxation, i.e., 2,597 personnel as of 2023, a 99.5% reduction compared to 2022. This indicated that CREHT’s heavy taxation function had already been essentially incapacitated (Bae, 2024).

In that same month, the Executive Office of the President officially announced to de facto abolish CREHT and integrate its real estate tax redistribution to local governments into the property tax (Jung, 2024), but due to fierce opposition from local governments, it retracted its announcement a month later. The Chief Presidential Secretary for Policy stated that CREHT, which initially fell under the category of wealth tax, had been distorted to serve as a means of taxation on the middle class (Lee, 2024). While economic media outlets reacted very positively to the proposed repeal of CREHT (Park, 2024), local outlets raised concern in unison about the worsening of local finances (Jeon, 2024). At the 22nd National Assembly’s Strategy and Finance Commit tee’s first general meeting in July, the Minister of Economy and Finance ultimately drew a line against the repeal of CREHT, pointing out the issue of local tax revenue (Cho, 2024b).

Ⅴ. Summary and Conclusions

This research has grave significance in that, based on the theory of gradual institutional change from a historical institutionalism perspective, it thoroughly explores how the idea of heavy taxation on unearned income from real estate has evolved over the past two decades while also shedding light on the corresponding dynamic institutional change. Taxation on land rent inherent in the land excess-profit tax (LEPT), which reflected the public concept of land, was rooted in the idea that all speculative land rent should be absorbed by the public. After the repeal of LEPT, this idea was revisited and revived as the comprehensive real estate holding tax (CREHT), but its original intent and spirit were significantly diluted as it evolved while reflecting the realities of taxation. Interestingly, its implementation as a specific form of policy was the result of gradual change through conversion, drift, and layering, combined with the mingling of various institutional traditions and norms.

In 1989, the Korean government embraced the Land Excess-profit Tax Act, which was considered the most stringent among the country’s three acts built on the public concept of land through conversion, aiming to broaden the application of the public concept of land and impose highrate tax on inefficiently utilized properties, such as idle land. In the early stages, the public welcomed the implementation of LEPT due to a nationwide outcry against real estate speculation and concerns over rising land prices. However, LEPT faced significant setbacks in its implementation, and due to some of its provisions that were deemed unconstitutional, LEPT was declared unconstitutional in 1994 and thus incapacitated. As the real estate market faced a downturn in the aftermath of the 1997 financial crisis, LEPT faded into the pages of history.

Regarding LEPT, it was deemed that there was a large discrepancy between its original intent and how it was executed in practice. With the lack of specific tax criteria for unrealized land rent income, which was understandable, the policy allowed for a high degree of discretion on the part of taxing authorities, coupled with implementation setbacks, resulting in overwhelming complaints beyond their capacity. Given that it was challenging to precisely determine whether or not a certain development activity had affected the generation of development gains in neighboring land, the authorities opted to adopt the normal land price increase rate as a benchmark. However, this approach could not effectively detect the effect of certain types of development activities, which also resulted in side effects, such as forcing land use by genuine land users at the cost of easing tax resistance. Consequently, LEPT was said to have failed to achieve its original purpose of recapturing development gains.

Additionally, the authorities failed to properly respond to landowners' tax evasion attempts through excessive temporary construction and makeshift land use. Moreover, their attempt to construct 2 million houses overheated the construction market, resulting in material supply disruptions and wage increases (Son, 1994). In an attempt to promote the effective use of land, which was the initial purpose of introducing LEPT, the authorities allowed for the indiscriminate construction of temporary structures.

This eventually led to the overheating of the construction market, which ironically contradicted its other aim, i.e., preventing real estate speculation.

Afterward, this idea of heavy taxation persisted as the Roh Moo-hyun administration implemented CREHT through conversion, in which the heavy taxation function of LEPT was restored, and the property tax function was enhanced while retaining the functions of the existing comprehensive land tax. When first introduced, CREHT attracted nationwide support from the public as it was recognized as a wealth tax, but soon, it faced tax resistance. Attempts to further strengthen CREHT in response to the rising housing prices in Seoul and the Metropolitan Area, coupled with the expansion of the tax base due to the increase in the assessed value, led to widespread opposition across even the low- and middle-income classes. This was followed by the Constitutional Court’s ruling of unconstitutionality, resulting in the incapacitation of CREHT.

Ten years from then, the Moon Jae-in administration revisited the idea of heavy taxation on real estate in response to the sharp rise in housing prices. As a result, however, the number of individuals subject to CREHT increased, sparking fierce tax resistance. Later, the Yoon Seok-yul administration attempted to incapacitate CREHT's heavy taxation function in the process of fulfilling its campaign promises but still has difficulty completely repealing CREHT because it is closely linked to local government finances.

In summary, the idea of heavy taxation on real estate has persisted in various forms, but its underlying context has gradually evolved while constraints imposed by other policies have continued to arise. Now, the following three conclusions can be drawn.

First, the idea of heavy taxation on unearned income from real estate has been implemented in the forms of LEPT and CREHT, undergoing cycles of introduction and withdrawal. At the time of the implementation of LEPT, this idea was introduced, in part, based on the concept of taxation on land rent, which was built on the public concept of land. Over time, however, its role in regulating the real estate market became significantly prevalent because more attention was given to LEPT’s punitive effect against real estate speculation as real estate prices surged. However, criticism continued against LEPT as the number of individuals subject to it increased, indicating that, in a way, LEPT had consistently been perceived as a wealth tax. This demonstrates that while LEPT and CREHT differ in what tax criteria apply and how they work, both are linked to the idea of heavy taxation from a long-term perspective.

Second, from an implementation perspective, CREHT, in which the idea of taxation on land rent was diluted to some extent, remained more stable than LEPT, in which the idea was thoroughly adopted. This demonstrates the flexibility of CREHT achieved through the layering process. Despite being followed by a range of follow-up measures to address its limitations, LEPT was eventually repealed. In contrast, in the case of CREHT, it was possible to either disable its heavy taxation function when it did not suit the situation or enhance the function when necessary. The use of LEPT was tied to specific objectives, such as taxation on land rent income and the recapture of development gains, but there was not much to do because it was difficult to determine and assess development gains in an objective manner. However, by inheriting the functions of both the comprehensive land tax and the property tax, CREHT served as a means of preventing real estate speculation by taxing the portion exceeding the tax base. Therefore, CREHT could be operated flexibly in response to public opinion or economic conditions. It is deemed that even if CREHT was repealed, the idea of heavy taxation on real estate inherent in it could be implemented within the property tax.